INTERVIEW Dec 2025 Gwen Evans: The Space Between

David Hancock

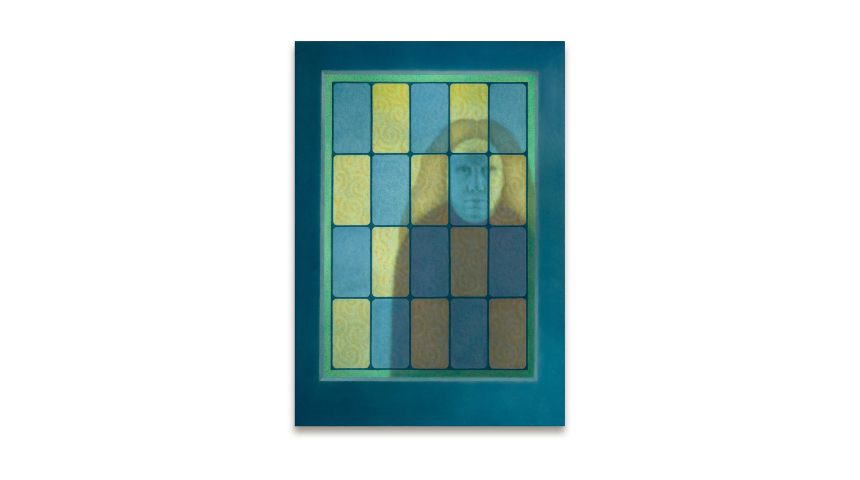

Gwen Evans 'Visitor' (2025) oil on canvas 105 x 128 cm photo Michael Pollard

In the run-up to her solo exhibition at Monti 8 Gallery in Rome, David Hancock visited Gwen Evans at her studio at Paradise Works, Salford to view the body of work that will form the entirety of her show. The five new paintings that Evans had been working on over the past six months were displayed around her small studio, while an accompanying series of framed drawings were propped against the wall. Encountering the work in this setting, alongside sketches in both oil and pencil, offers a valuable insight into Evans’ practice.

Earlier this year, Gwen Evans and I established an ad hoc crit group with five other Northwest–based painters, involving regular studio visits to discuss our respective outputs. Our conversations revealed shared interests and recurring themes within our work, which we explore here.

David Hancock: You have a show coming up in December at Monti 8 Gallery in Rome. You have created a new body of work exclusively for this exhibition. Could you talk about your plans for the show and what might the audience expect?

Gwen Evans: This latest body of work presents a series of paintings and drawings depicting anonymised figures and peeping silhouettes that interrupt the stillness of domesticity. Facial features, a reassuring reference point, are removed or obscured, and characters are unreadable with their motives unknown. I aim to provoke a sense of unease in the viewer, leaving them to question the character's intentions or whether something sinister is about to unfold.

I’m interested in the uncanny, especially in relation to the home. As Freud outlines, the uncanny can arise when something strikes us as familiar yet alien at the same time. By depicting patterns or textiles associated with the domestic, such as tablecloths and quilts, I wanted to evoke ideas around homeliness and comfort, which is in direct opposition to the unsettling narratives and anonymised figures. Some of the imagery is influenced by my childhood home, like the quilt in the painting Visitor, made by a family member, or is a nod towards Welsh culture, like the love spoon in Impasse.

Boundaries and thresholds are repeated throughout the work in the form of windows, doorways or curtains, giving the impression these figures are “in-between” and adding to the sense of uncertainty. These liminal spaces continue beyond the confines of the painting, with the edge of the canvas acting as the edges of windows and doorways. In other works, protagonists interact with someone beyond the painting, positioning the viewer as a participant or voyeur in the unfolding narrative.

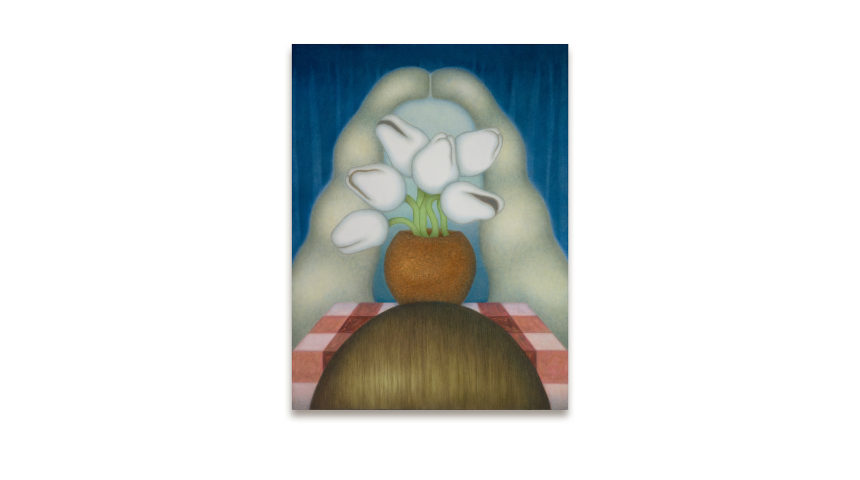

Gwen Evans 'Threshold' (2025) oil on canvas 70 x 100 cm photo Michael Pollard

DH: There are two really interesting aspects of your work that I’d like to explore further, particularly in relation to my own work. Firstly, there's the uncanny, which I think is something that we are both really interested in exploring, but also boundaries and thresholds, which I'd like to discuss first. Within my own still lives, I have always been interested in the idea of a rupture within the space of the still life. This has often taken the form of a photographic insertion into the still life, so that there are two planes coming together. One is the physical still life, which is clearly made of 'real' objects that to some extent are representations of 'real' things, such as the dolls, or ceramic animals, but then I also usually insert a photographic image, usually of model taken from a fashion magazine. The model is a 'real' person, but in the still life, they are a two-dimensional image, so not physical. The still life also references the artist, who will paint the scene before them, and the studio in which this takes place, so I am also referring to an interaction alluded to but unseen by the viewer. I am; therefore, really intrigued by what you refer to as the liminal space beyond the confines of the painting. Would you like to expand upon that?

GE: I want the gallery to almost become this transitional space, where the audience is drawn into the work, or perhaps the worlds within the paintings spill out into the gallery itself. In my painting Housework, the edges of the canvas mirror a window ledge, and the use of perspective almost makes you feel like you could step into the work. I also think the scale gives the illusion that the window in Housework could physically exist in the gallery. As you mentioned, this idea of two planes coming together, that of the pictorial and the real world, appears in your work, where you insert a photographic image into a still life of tangible objects.

I like how you described a kind of rupture that happens in your work within the space of the still life. This idea of a break or disturbance in the picture plane is also reflected in my painting Threshold, where the figure appears to acknowledge a presence beyond the frame, almost breaking the fourth wall and inviting the viewer to step into the scene as both participant and observer.

DH: Within your paintings, there is a marked sense of the Uncanny. You represent everyday scenes such as hanging out washing, answering the door, or looking at oneself in a bathroom mirror, but in every one of these mundane acts there is a tension that is unsettling. It is really difficult to pin down, such as the way a head merges with a plant in passing, or a glance away from the mirror. You appear to capture these fleeting moments, and in this instance provide a sense of how this threshold to the uncanny is present within our routine existence.

Gwen Evans 'Housework' (2025) oil on canvas 70 x 100 cm photo Michael Pollard

GE: That’s exactly what I wanted to push more in this body of work – how everyday rituals and familiar environments can become uncanny. In his essay on the uncanny, Freud describes it as “a class of frightening which leads back to what is known of old and long familiar”. I think the home and the rituals we perform within it is a fertile space for the uncanny to take shape. It only takes a slight shift from the ordinary for something to start feeling strange. I also like that the figures project this feeling of malaise whilst performing these domestic tasks, which adds to the unease in the work.

The depersonalisation and pallor of the figures aim to evoke that same unease, particularly in my depiction of hands, where the absence of fingernails makes them appear quite doll-like. Freud suggests that an unsettling feeling can arise when we’re unsure whether something inanimate might actually be alive – like a doll or a wax figure. I think this is an interesting connection between our work. While I strip away individuality until my figures almost resemble dolls or automatons, your figures begin as dolls that you then imbue with human qualities. In both cases, the figures exist in this in-between space – somewhere between the living and the mechanical – and I think that tension is what gives rise to the uncanny in both of our practices.

Most of the environments in my work are liminal, and liminal spaces themselves are closely tied to the uncanny. Firstly, on a physical level, such as transitional spaces that feel off – like endless hallways or familiar settings out of context, like a supermarket devoid of people, but also on a psychological level. They represent a kind of in-between state, an unsettled frame of mind where things don’t feel entirely stable. I think that sense of uncertainty is a key part of what makes something uncanny. In my work, the figures are placed in these vaguely familiar domestic spaces, but they lack context. They also often depict transitional spaces, like thresholds or windows, that suggest the possibility of crossing into something unseen.

David Hancock ‘The Time I Drift Away’ (2025) watercolour on gesso panel 50 x 70cm

DH: I think one of the ways you emphasise this is through your colour palette. In many of the works, you appear to mute one of the primary colours. For example, in Housework, there is very little red, if any. You shift the muted colour throughout this body of work, and I think your choices add to that sense of the uncanny. I’ve also been attempting to limit the range of colour in my own work as a way to tie a body of work together. Although I haven’t restricted my palette as such, I have been limiting the colours of the objects that I include in my still lives. For instance, I’ve only selected objects of a single colour so that one still life might feature only red objects, another only blue. I remember seeing Robert Therrien’s installation RED ROOM (2000-07) at Tate, in which he filled a gallery space entirely with red objects. Many of these were domestic household items, but their singularity of colour transformed them, en masse, into something rather uncanny. In both our practices, limiting the palette seems to shift everyday objects into something far more disconcerting.

GE: Although I have started to introduce a bit more colour recently, I usually like to use a repetition of green, red and blue. But like you said, I do try and keep the palette quite muted. I think that restraint brings a sense of stillness to the work.

The greenish, almost sickly tone of my figures comes from the verdaccio technique I use, but it also connects to ideas surrounding the uncanny valley. First introduced in the 1970s, this concept relates closely to Freud’s theories of death and the uncanny. I’ve always been drawn to monochromatic work, and so I love Robert Therrien’s installation RED ROOM. I agree – that almost relentless repetition of a single shade of red pushes the work into the uncanny, while also giving it this charged, suffocating intensity. As I painter, I really admire how Lisa Yuskavage floods her work with one dominant colour, contrasting realistic elements in the painting with large, abstracted areas of colour – almost similar to colour field painting. I especially like her painting Changing (2005).

Gwen Evans – The Space Between is at Monti 8 Gallery in Rome from 4th December 2025 - 24th January 2026.

Gwen Evans 'Checkpoint' (2025) oil on canvas 80 x 60 cm photo Michael Pollard