INTERVIEW Jun 2025 Lela Harris: Memory, Resistance and Ink

Harpreet Kaur

Lela Harris Assembly Arts May 2025 photo Ginny Koppenhol

Lela Harris is an artist originally from Manchester and now based in Cumbria. Using historical research, documentary photography and a range of media, Harris creates often monochrome, portrait-based work that seeks to reveal the hidden lives and histories of marginalised or forgotten people. Harris has recently been recognised for two nationally important awards for her sensitive depictions of ordinary individuals: a finalist for the Museums Association Decolonisation Award 2023 for her ‘Black Lancastrians’ exhibition at Judges’ Lodgings Museum, Lancaster, and Runner Up in the V&A Illustration Awards 2022 Book Cover Category for her work on the first illustrated edition of ‘The Color Purple’ by Alice Walker, published by the Folio Society. Here, writer and cultural consultant, Harpreet Kaur interviews Lela Harris for the June issue of the Fourdrinier.

Lela Harris: Lost, Found, and Fully Seen

‘Lost and Found’ marks the first solo exhibition by British artist Lela Harris – a powerful and personal body of work that sees the artist step into the spotlight with her own story. Growing up in Manchester, Harris’s childhood was shaped by adversity, creativity, and moments of escape. In this new series, she draws from memory – reconstructing hazy, half-held images and emotions in delicate ink drawings layered across sheets of paper. The result is a quiet and compelling exploration of identity, dislocation and the longing for belonging.

While this is the first time Harris has centred herself in a show, she is no stranger to telling powerful stories. In her 2022 project Facing the Past, commissioned by the Judges’ Lodgings Museum in Lancaster, she created portraits of Black individuals enslaved during the 18th century – people whose names and stories had been all but erased. Through meticulous research and sensitive portraiture, Harris illuminated their humanity and underscored the city’s role in the Transatlantic Slave Trade. The series earned a nomination for the Museums Change Lives Decolonising Museum Award from the Museums Association.

Harris’s practice extends across illustration and portraiture. In 2021, she was commissioned by The Folio Society to illustrate Alice Walker’s The Color Purple – a landmark novel that has long inspired her. She is currently working on new illustrations for James Baldwin’s Giovanni’s Room. Self-taught, Harris draws influence from artists such as Barbara Walker and Lynette Yiadom-Boakye – women whose work foregrounds Black experience with intimacy and scale.

Working primarily with pencil, graphite and ink, Harris’s drawings are subtle, poetic, and full of feeling. Her technique is simple but emotionally layered – each mark carefully placed to honour the complexity of the people and histories she engages with. Whether reflecting on the distant past or confronting the fragments of her own memory, Harris’s work speaks with honesty, care, and quiet determination.

This interview, conducted shortly after the opening of ‘Lost and Found’, explores Harris’s creative process, her influences, and the deeply personal journey behind this new chapter in her career.

Harpreet Kaur [HK]: ‘Lost and Found’ is your first self-initiated exhibition. What made you feel ready to tell your own story now?

Lela Harris [LH]: Over the last couple of years, I’ve been responding to commissions—learning about historical figures and celebrating them. But when I worked on the Black Lancastrians project, I realised I didn’t know much about myself. I’ve since done a DNA test to explore my paternal side.

Life was rough with my mum when I was growing up. I hadn’t processed a lot of it – it felt doom and gloom. But then I started remembering these little flashes of nice moments from childhood too. I realised it was OK that it was difficult – it doesn’t have to be a depressing exhibition because of that.

This show is about the hope you find for yourself, and how that carries through to who I am now as an artist. Some pieces were emotionally challenging because they brought up things I hadn’t fully dealt with. But most of the time, it’s been enjoyable – like piecing together my own photo album.

Lela Harris Two Sisters (2024) ink and pencil on watercolour paper 84cm x 120cm approx. Photo Lela Harris

HK: Let’s talk about your process. The way you layer multiple sheets of paper for a single image is so distinctive. Where did that come from?

LH: I like working on panels for a few reasons. Creatively, it feels like piecing together a memory—each section gives me time to reflect. People have said it looks like unfolding an old, crumpled photograph, which fits because memories can be fragmented too.

Practically, I’ve got a small space, so working panel by panel suits me – I can store them easily, and if I mess one up, I don’t have to start over, which is great with ink since there are no second chances. It helps me relax into the process.

Also, with my full-time job and commissions, sometimes I only have time to finish one panel a week – but completing even that one gives me a real sense of achievement.

HK: You work almost exclusively in monochrome. Why?

LH: I think I love monochromatic. I feel most at home working that way because it frees me up to be more responsive – I overthink colour. I love working in colour too, but I find it more stressful. I feel more relaxed working tonally.

When I approach a reference, I’m interested in it tonally first – more than colour or composition. With ink, I like how it’s got a life of its own. It does things on paper you can’t predict, and I kind of like that unpredictability. I also like that it’s not neat – you make lots of mistakes, but you can turn them into something else or embrace them. I quite like that quality.

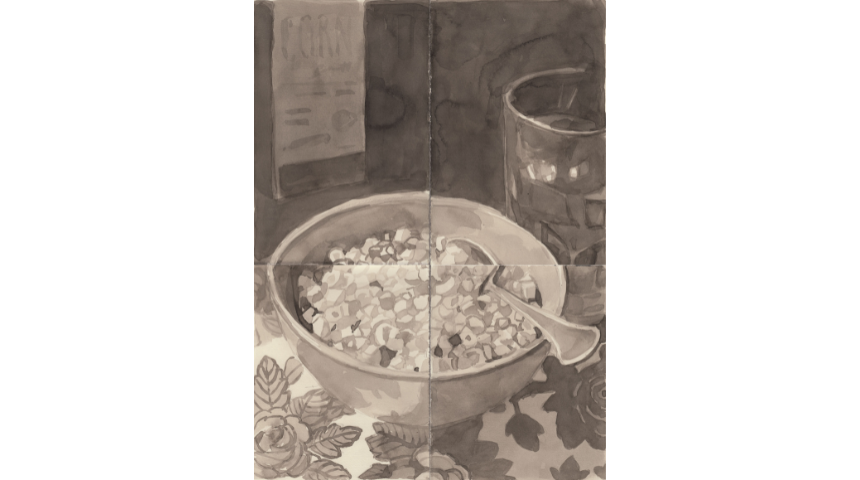

HK: I’d like you to tell me a bit more about these pieces from the exhibition that resonated with me; Cereal Days, Two Sisters and Turning Point.

LH: Cereal Days is my favourite piece from the show. It’s rooted in this odd little memory about cereal, shoes, and Mondays – when my mum would go to the post office for her benefits, and we’d get the week’s shopping. That was when we got treats, like a box of cereal. You had to be quick, or it’d be gone that same day.

Technically, I love the patterns in that one – the tablecloth, the reflection on the porcelain bowl, the cereal itself. It’s an imagined mix of Rice Krispies and cornflakes. I let go of strict references and made-up parts of it, which I don’t usually do.

But now, I look back and realise we were in food poverty. Those exciting cereals marked the only day we had luxury. We drank sterilised milk from vouchers – fresh milk was a rare thing. So, while it feels nostalgic, it’s also about survival and what food meant to us then. It reflects that time in the 1980s – and sadly, that reality is back for many families today.

Two Sisters is me and my older sister – she’s doing my hair and I’m the one looking miserable. My mum, who was white Irish, didn’t know how to manage my afro. My sister, who has straight hair, would do it for me so I didn’t look a mess at school.

It was always a battle – I didn’t want my hair done, and she didn’t really want to do it – but she cared that I’d be okay. I’d sit between her knees, and she’d tug and tap me to sit still. I hated it back then, but looking back, it was this amazing act of love. That moment of physical closeness was rare – we weren’t a hugging family. But with her, that was a moment of feeling safe. She saw the piece at the show and asked, “Is that us?” I said, “Yeah, and I know you didn’t mean to hurt me.” We both laughed.

Lela Harris Cereal Days (2025) ink and pencil on watercolour paper 42cm x 60cm approx. Photo Lela Harris

I love choosing titles. I keep a list on my phone – words or snippets I come across from reading, conversations, or songs. Sometimes I’ve had a title for years before it finds its painting.

Turning Point is about how much we moved as kids – private rentals across Rusholme and Moss Side. I counted 11 different homes before I was kicked out at 16. Each move felt the same—the same alleyways, the same back-to-backs. The title reflects those constant shifts.

It was hard to paint. I don’t normally do buildings, and making it feel messy but still like a house was tough. Maybe that feeling of unsettledness came through in the process. I don’t like moving, and painting it brought that emotion back.

HK: You mentioned that you didn’t start drawing until your late 30s. That’s remarkable. How did it all begin?

LH: I broke my wrist and couldn’t knit, so my husband bought me a painting class at the Brewery Arts Centre in Kendal. I was around 39 or 40 then. I started doing homework for the class and sharing it on Instagram, just like a diary. People began asking to buy the pieces – and that was a bit wild!

Instagram became a lovely space for connection – chatting with other artists, both self-taught and more established. Then, out of the blue, the Folio Society got in touch. I genuinely thought it was a scam! I was googling the art director to check it was real. It was. They told me Alice Walker had seen and liked my work – and they asked me to illustrate The Color Purple.

I had to submit trial drawings; I was up against an established American artist. Six weeks later, I got the call – I’d landed the job. That was a turning point.

Since then, I’ve mostly taught myself – books, YouTube, just trying things out. Lockdown really helped. I had time to study artists I admired – Rembrandt, John Singer Sargent – just doing lots of observational studies and going from there.

HK: Do you feel your practice is political? You often deal with underrepresented narratives and histories.

LH: I don’t really approach it as political. When I worked on Black Lancastrians, Lubaina Himid came to the opening and said I’d carried so much weight with real sensitivity – but at the time, I wasn’t thinking about the impact in those terms. I focused on the people in the portraits, not solely the narrative of slavery, because I didn’t feel I could speak to that directly – I wasn’t there. Instead, I wanted to give viewers a starting point to do their own historical research.

I try not to put pressure on myself to cover everything. The work becomes the entry point, and it speaks for itself. Black Lancastrians is now part of the permanent collection at Judges’ Lodgings Museum, and we were runners-up for the Museum Association’s Decolonising Award last year. That shows the impact, but I must be careful not to get too wrapped up in the politics while making the work – it would be overwhelming.

Lela Harris Turning Point (2025) ink and pencil on watercolour paper 42cm x 60cm approx. Photo Lela Harris

HK: Do you feel connected to the people you draw, even when they're historical or anonymous?

LH: Totally. When I was working on Black Lancastrians, my tiny studio was filled with the portraits at various stages. It felt like hanging out with friends – “Morning, Thomas,” “Not today, Francis” – sometimes I’d turn one to the wall and focus on another. I’d researched as much as I could about their lives, and that connection stayed with me.

When the portraits left for the museum, it felt a bit sad – they’d been part of my space for so long. But the most powerful moment came when they were projected onto the outside of Judges' Lodgings during a public event. Twenty thousand people came over the weekend. Nobody knew I was the artist, so I got to stand in the crowd and hear people say, “Oh, they’re Black Lancastrians.” It was incredible to see the community take pride in them as historical figures from Lancaster.

HK: How did it feel to work on The Color Purple? Was there pressure in responding to such an iconic narrative?

LH: Once I got over the shock, I had to submit a trial drawing – but I’m an overachiever, so I sent three. They accepted all three, which covered half the commission already. That first stage was relaxed because I didn’t think I’d get the job. But once I did, the fear set in – I wasn’t sure I could pull it off.

There was a lot of dog walking while I processed it all and figured out my approach. I spent time researching – digging into archive photography of the American South, plantation workers, and anything I could find. Then I got to work designing the cover, the box, and six internal illustrations. I really got into it at first, but by the end, I’d hit a wall – I’d run out of drawing juice.

Thankfully, Raquel, the art director at the Folio Society, was incredibly supportive. If something wasn’t quite right, like missing a feather from a hat, she’d flag it – but always with encouragement: “You’ve got this.”

Seeing the final version was amazing. It looked nothing like my scrappy originals. And then to find out the book cover was runner-up at the V&A Illustration Awards – it was surreal. I’ve just finished my second book now, and while it was still hard, it wasn’t quite as daunting as The Color Purple because this time, I had a process.

HK: You’ve mentioned Barbara Walker and Lynette Yiadom-Boakye – what about their practices speaks to you most?

LH: I really admire both. They’re incredible artists. I love the scale they work at, the way Barbara experiments with different mediums, and how Lynette uses found imagery to tell stories – not overtly political, just her narrative. Her titles are obscure and poetic, which has inspired me to be more thoughtful with mine. They’re both quietly epic – just cracking on and doing amazing things.

HK: What has the response been like to Lost and Found?

LH: I’ve been surprised, delighted and a bit overwhelmed. I thought it was quite a niche, personal show and wasn’t sure how people would connect. But it’s been amazing to overhear visitors reminiscing about their own childhoods or asking about the process. Social media response has been lovely too. Chatting to people in the gallery has made it feel worthwhile.

HK: How do you want your work to live on in people’s minds?

LH: I’d love people to feel a bit dreamy – open to possibility. I hope they leave not fixed on what they saw, but with their imaginations stirred, maybe thinking about their own memories or stories. Just open to different perspectives.

HK: Is there a story you haven’t told yet that you hope to explore?

LH: Oh, there are millions! But one thread I’d love to explore is Black history in Cumbria. I’ve done work in Lancaster, and I live here now. There’s this assumption the Lake District isn’t for brown people or that we’ve never lived here. But I’ve found evidence in the archives that says otherwise. It could open different conversations – about landscape, about wealth built on Black labour. I think there’s work to do there.

HK: Do you see yourself more as a portraitist, historian, storyteller – or a bit of all three?

LH: A bit of all of them. Right now, I feel like a time-travelling artist! I love digging into the archives – I didn’t realise I could combine my love of reading and drawing into a practice. I gave a talk recently and said, “I don’t know if I found the practice, or the practice found me.” But it works.

Lela Harris Bus Station Cafe (2024) ink and pencil on watercolour paper 84cm x 120cm approx. Photo Lela Harris