FEATURE Nov 2025 Floor to ceiling – 150th Anniversary Exhibition at The Atkinson

Jo Manby

Samuel Lawson Booth (1836-1928) Conway Castle (1900) oil on canvas 120.7 x 242.5cm courtesy The Atkinson

The Atkinson Art Gallery holds a collection of over three thousand works of art spanning five centuries. Until Saturday 21 February 2026, visitors to The Atkinson can soak up the aesthetic experience of witnessing the whole collection on show at one time in a historic salon hang that cuts across contemporary curatorial norms and upturns expectations of how an exhibition should look. Far from minimal, this is a sumptuous treat for art lovers of all persuasions. the Fourdrinier editor Jo Manby had the opportunity to visit the gallery and talk to its curators about the wide-ranging art on show.

https://theatkinson.co.uk/exhibition/150-anniversary-exhibition/

Walking into the main gallery space at The Atkinson, the temptation is to feel as if you are in a time-warp, or at least entering a stage set for a costume reconstruction of a scene at the Royal Academy circa 1890. Immediately the showstoppers loom out of the walls. William Atkinson, Esq. (1797-1883) (1870) by Lowes Cato Dickinson (1819-1908) at two metres 60cm in height; the luminous landscape, Conway Castle (1900) by Samuel Lawson Booth (1836-1928); Lilith by John Collier (1850-1934), based on the poem ‘Eden Bower’ by the Pre-Raphaelite painter and poet, Dante Gabriel Rossetti; and Bull, Cow and Calf by noted painter of cattle Thomas Sidney Cooper (1803-1902), oil on canvas, nearly two metres wide.

But look around – there are a host of fascinating, notable artists alongside. Small works by leading figures of the last century and a half emerge like faces in a crowd, stars Walter Richard Sickert, Vanessa Bell, Charles Ginner, Laura Knight, John Bratby, Anne Redpath, Frank Dobson.

Here in the 150th Anniversary Exhibition is an opportunity to see a collection in its unadorned reality, unmediated by curatorial themes or rationales. This show has not been curated as such. Of course it has, in the sense that much time and expertise and effort have been expended in its preparation. But, in effect, in a condensed version of rather more complex events, the technical staff at The Atkinson basically took the collection and hung it bottom to top, left to right, all round the room, apparently without a hanging plan. Arguably the only theme is the combined tastes of two centuries of collectors and of British museums collecting policies. It’s a free for all – but a glorious one. Finding a gem like Augustus John’s The Red Toque (n.d.) or CRW Nevinson’s Limehouse (1913) hiding in the mass of paintings is as thrilling as spotting Queen Elisabeth II dressed in civvies among the surging crowds of VE Day.

John Collier (1850-1934) Lilith (1887) oil on canvas courtesy The Atkinson

Areas of particular focus include 17th and 18th century portraits, such as those by Peter Lely, Arthur Devis and Joseph Highmore. An extensive ensemble of Victorian watercolours and oils features major British artists Steer, Landseer, Cotman and Sargent. There are small groups of work from 20th century British movements such as the Scottish Colourists, the Bloomsbury Group, the English Futurist CWR Nevinson and modernists Paul Nash and William Roberts, along with a good selection of northern artists including LS Lowry, Theodore Major, Helen Bradley and Adrian Henri. Added to this are European painters from the Paris Salon and 19th century Dutch art scenes.

The large scale paintings were mainly acquired during the nineteenth century, a period in which museum collecting was fairly informal and unregulated. The painting of Conway Castle was a gift from T. Talbot Scarisbrick in 1900, the year it was painted; the portrait of William Atkinson, who is depicted holding the plans for the art gallery, was a gift from Miss Mary Hulse in 1913; Lilith was probably bequeathed to Bootle Art Gallery before 1944 through Frederick Corlett Johson’s connection with the town. Born in 1871, he was a family member of the Johnson dyers and cleaners empire. Lilith was then transferred to The Atkinson in the 1970s, along with numerous other works. ‘Lilith has become the icon of The Atkinson. When she isn’t on the wall as part of one of our exhibitions, we have to put something out to explain where she is!’ Joanne Chamberlain, Heritage and Participation Officer at The Atkinson explained to me. ‘She is our most loaned painting from the collection. The loans include Germany, Italy, and Spain. Anything with a local connection is always a big crowd pleaser too.’

In 1845 the Museums Act enabled local museums to be established, funded by a small tax, followed by the 1850 Public Libraries and Museums Act. Philanthropists such as Andrew Carnegie and Henry Tate continued the work in the wake of subsequent acts. The Atkinson Art Gallery opened in 1878 due to the benefactor in the portrait, William Atkinson, donating generously to Southport Corporation. A year later, the gallery, which originally opened without a permanent collection, was suddenly enabled by the gift of 18 oil paintings and 21 watercolours from a local collector, Miss Ball. Subsequently, and until 1967, the gallery made regular purchases from its annual Spring Exhibition to augment this founding collection.

The 1963 British Museum Act granted disposal powers with limitations and legislation relating to gifts, bequests and purchases. The Friends of The Atkinson Art Gallery purchased works for the collection, most frequently during the 1950s and 1960s. In the same borough as The Atkinson, the Bootle Free Museum and Art Gallery had opened to the public back in 1888 with fine and decorative arts, local and natural history, costume and silverware, together with the Goodison Collection of Egyptology. When this museum closed in 1974, most of the holdings were transferred to The Atkinson Art Gallery and (then) Botanic Gardens Museum. More recently, the Museum & Galleries Act 1992 controls how proceeds from selling assets can be used; while the setting up of the Museums Association and its Code of Ethics facilitates guidelines for contemporary collecting practices and mitigates against illicit trade.

It is noticeable that there are quite a few areas of particular interest in the collection, such as portraiture and Dutch painting. I wondered about the story or history of the collection policy at The Atkinson, and whether it mainly been a matter of personal curatorial taste at the time of collecting. ‘Initially the gallery opened with no art collection which was why the first salon hang was of loaned artworks. Some of those lenders bequeathed their art collections to The Atkinson and other local patrons followed suit,’ Exhibitions and Learning Officer, Jemma Tynan explained. ‘As the collection was starting the curators had a budget to purchase works, the Friends of The Atkinson Gallery helped purchase works and the curators were able to purchase through grant funds like the V&A. I’ve been told the curators were going out to visit artists at their studios and buying pieces on speculation, and we know they would purchase from the exhibitions held at The Atkinson such as the Spring Exhibition so we have local artists represented in the collection.’

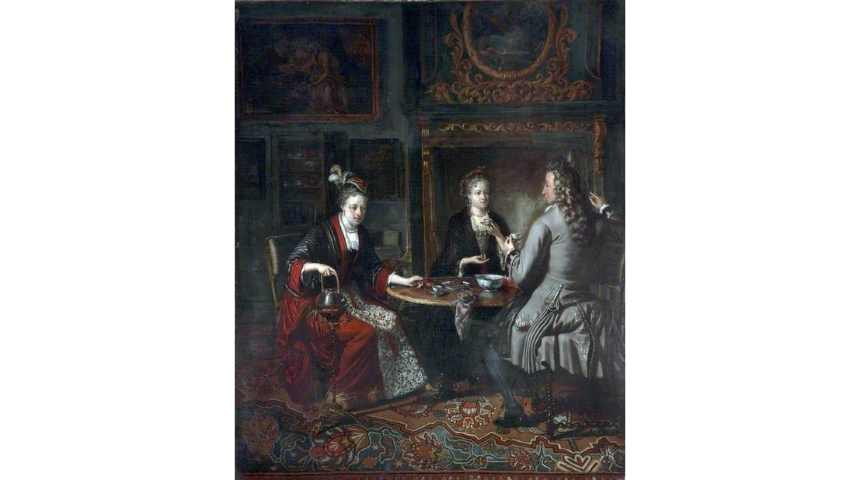

Matthijs Naiveu Afternoon Tea in Holland (c1720) oil on canvas 88.9 x 73.6cm courtesy The Atkinson

Among the Dutch paintings you can find Amsterdam, The Netherlands by Willem Koekkoek (1839-1895), an oil on canvas acquired in 1970, which depicts a canal scene with the hallucinatory, pin-sharp clarity common to Dutch painting – you can almost taste the cold, clean air, and there is a faultless harmony in the composition as it traces a continual turning of triangles, rectangles, and the occasional curve to set them off. In Matthijs Naiveu’s painting, Afternoon Tea in Holland (c1720), Jacob Cromhout and his wife and niece Elisabeth Jacoba Cromhout, who lived between 1671 and 1737, are pictured by the artist taking tea in their franse sael, or French salon. Tea was an expensive imported treat and it is dealt with ceremoniously with a small kettle and tiny blue and white tea service. Around the salon are ornate frames and a costly carpet.

Tynan had mentioned to me when I visited that Young Girl in Cream Dress (c1910) by Laurence Koe (1869-1913) had been conserved, leading up to the 150th Anniversary Exhibition. It was ‘restored and reframed with support from the Ulrike Michal Foundation For The Arts (UMFFTA), Arts Society Southport, The Atkinson Development Trust and donations from our wonderful visitors,’ said Tynan. ‘It had several holes and was very dirty so was sent to conservator Harriet Owen Hughes. She worked her magic before framer Germaine Denn finished the process. I have started to refer to the work as Young Girl in a White Dress as that is how it is referred to in our previous records, I think it became cream dress due to the layer of dirt!’

I wondered whether this work had been chosen for conservation because it was a favourite with visitors, but as Tynan explained: ‘We don’t think it has been on show since it came into the collection due to the amount of damage. The decision to restore it was made because whilst it was in a poor condition it wasn’t beyond repair, and we are committed to caring for and conserving our collection for the enjoyment of all. In the last decade we have been able to conserve several pieces from the collection for exhibition including Triumph of Art by Nicolas Pierre Loir (1624-1679).’ Tynan described the way that fundraising and the support of the gallery’s partners are a key part of this process. ‘We hope Young Girl In A White Dress will become a new favourite and feature in many future exhibitions.’

During the twentieth century, financial considerations appear to have reduced the size of the works purchased. In the early, pre-war part of the century, there were still some sizeable additions to the collection. Alfred James Munnings’ (1878-1959) Trooper in Full Marching Order (n.d.) was purchased in 1938. A large-scale, highly competent oil painting, 99 x 125.1cm, it depicts a soldier fitted out for the Western Front, mounted on a well-groomed horse with a trace or chaser clip. It could take a cavalryman 12 hours to clean a horse and its harness, so good grooming was essential – this also prevented skin infections and allowed inspection for wounds or sickness. Here, the horse’s belly has been clipped to avoid gathering mud. Munnings has had both high and low points in fashion and is generally sidelined these days as a conservative academician, but his skills are clear to see and make his work very popular with many people.

William Orpen The Eastern Gown (1906) oil on canvas 89 x 73.5cm Courtesy The Atkinson

However, post-WW2, a different set of criteria and strictures were in place. The financial collapse of the 1930s, the necessity of postwar reconstruction into the 1950s and 60s meant smaller budgets. However, it is also important to acknowledge the key role of culture and its continuity in the wake of the economic and sociopolitical upheaval of wartime. Libraries and galleries come into their own at such times and are part of the social recovery process. Acquisitions policy became increasingly professionalized during the 1970s, 80s and 90s, with focus on filling gaps in collections and on making objects and artefacts accessible to a wider audience. The UK’s Museums Association was actually founded in 1889, and sets ethical standards for professionals working within the sector. In the first decade of the 2000s, following universal free entry to museums, visitor figures effectively doubled, showing that there was an ample audience.

‘Our current collecting policy focuses on enhancing the collection we have and addressing the balance of gender and cultural representation,’ says Chamberlain. ‘We do have a good number of female artists in the collection but, as with the majority of art collections where traditionally collected artworks were predominantly by white male artists, there is an imbalance that can be worked on. We are also looking at new media, for example collecting more digital artworks.’

There are numerous portraits in the collection. The Gardener by Neville Lewis (1895-1972), a small oil on board portrait; Ian Grant (c1935) by Raymond Lintott (1893-1949), a moderate sized oil on canvas portrait purchased in 1952; Glyn Philpot’s Mrs Eva Lutyens (1935-36) a large oil on canvas; the refined painting Elissa Landi by Howard Somerville (1873-1952), a gift of the Misses Adamson, sisters of the artist, in 1955; Self-Portrait by Adrian Ryan with its loosely brushed grey background warmed by a touch of yellow ochre; John’s The Red Toque which shows an interesting character whose sideways gaze indicates an enquiring nature; curious and creative, her choice of hat and green-blue and orange flowered scarf and blouse suggest a quietly flamboyant woman.

Among the many twentieth century interiors are Walter Richard Sickert’s (1860-1942) Sinn Féiners, oil on canvas, a gift from F Hindley Smith in 1924, and Scottish Colourist Samuel John Peploe’s (1871-1935) Studio Interior, purchased 1939. Landscapes include Cap Brun, France (1929) by Frank McEwan, a small oil on canvas landscape presented to Bootle Art Gallery in 1931 and transferred to the Atkinson in 1974. This painting has a light-filled, post-Impressionistic atmosphere, radiating sensory delight, a verdant landscape under a sky quivering with heat and the aerial perspective of blue distant hills; a house shuttered against the heat of the day, a vegetable garden, the promise of delicious meals.

Thomas Sidney Cooper (1803-1902) Bull, Cow and Calf oil on canvas 135 x 197cm Courtesy The Atkinson

Chideock, Dorset by Charles Ginner, purchased 1963, is again small, 51 x 43cm. Ginner is adept at blocking in the disparate elements of a landscape or scene with tight, well-defined areas of colour, leaving nothing to chance – the effect is of a well composed, utterly believable scene of great aesthetic impact. He creates a whole world in a single painting. It’s like watching world building; measured, pictorial perfection. This composition has a mass of foliage on the left and an outpost of terraced houses on the right, of a central core of a road that leads the eye into the heart of the village and on up to the green hills in the mid and far distance.

On the Way to Maspalomes, Canary Islands, Spain, just under a meter wide, oil on board, purchased 1962, by Scottish painter Ann Redpath (1895-1965), is a fine example of Redpath’s capabilities. It gives the impression of a scene glimpsed from a car at night, a great sweeping open foreground of expressive and heavily worked red, black and silver paint; a landscape semi-perceived in shadow with buildings looming out of it in shades of white and dove grey. In the far distance an electric blue lights up parts of the thunderous sky.

Urban cityscapes find their way into the collection: there is the Lowry street scene, a white street flanked by black and red gable ends, a gathering of people, a grey mill rising like an apparition at the end of the street: face-on perspective with the vanishing point dead centre, Lowry makes the perspective the way in, compels the viewer to enter the scene, to stand around with the groups of men in caps, newspapers in hand, women and children, have a natter with them, very down to earth. Nevinson’s Limehouse is diagonally intercut by fold-like divisions, an industrial scene of tarnished, corroded colours and oxidized, mineral tones. Richard Meaghan (b1970)’s City Line IV (2000) is a large scale oil on canvas, purchased 2001, where a dark figure seems lost in a haze of smog or mist, the road pale and wet and the steps forward uncertain.

My favourites, if I had to choose, include the oil on canvas Blackberries (1922) by Harold Charles Harvey, purchased 1928. One girl reaches up to pick fruit from a briar, the other stays a step or two behind, minding the basket, and caught in the act of eating the berries. With its autumnal backdrop of unruffled sky and green hills, it captures the idea of fleeting youth and the so-called idyll ‘between the wars’ of the 1920s. The other is the oil on board Two Miners by Roger Hampson, purchased in 1976, with its glowering sky and tall chimney, industrial grafters standing looking at the painter just long enough to be recorded before moving on, back to the grind, part of the machinery. These two paintings are in a way a world apart, showing the validity of all walks of life.

I asked Chamberlain whether curating a salon hang had been a fun but challenging exercise. ‘At first daunting, then back breaking and challenging. This is not how we hang artworks today. Our exhibitions usually have a narrative, and a specific choice of work is chosen to tell a particular story. Hanging in this way felt like really going against the grain. However, a couple of days into the installation it became fun. I was working with a great team and we got to throw the rule book out. It was a great experience and we thoroughly enjoyed it.’

The idea of the whole room as a time-machine with, instead of switches and buttons to press for, say 1925, it presents you with a series of images, each one a portal that will directly transport you into the creative imagination and vision of an artist who made that image in that exact year. Who sat and stared at the subject before them, or in their mind, and put it down on canvas, or board, or panel, with paints, and fixed it there, for you, the beholder. And The Atkinson collected all these individual portals and looked after them here for you, in this museum. That’s what museums are for. That’s why we will always need them. That’s why the destruction of art, artefacts and architecture is so devastatingly bad for societies. Not just for the society that’s suffering the destruction, but for all of us. And why opportunities like seeing The Atkinson’s 150th Anniversary exhibition are not to be missed.

This feature is supported by The Atkinson