REVIEW Sept 2025 Albert Richards at The Williamson Art Gallery, Birkenhead

David Hancock

Installation view of Albert Richards at The Williamson Art Gallery, Birkenhead (Photo: David Hancock)

To coincide with the 80th anniversary of Albert Richards’ death, the Williamson Art Gallery in Birkenhead is currently hosting a small retrospective of the Liverpool artist’s work, running until 20th December. FREE entry. Director of the Fourdrinier, artist, lecturer, and curator David Hancock reviewed the exhibition.

The Williamson, on the Wirral, is something of a hidden gem. A good 15-minute walk from Birkenhead Central and set within a residential estate, the museum houses two significant permanent displays. It boasts the largest public collection of Della Robbia pottery in the UK, while the Maritime Room contains numerous scale models of ships built by Cammell Laird in Birkenhead. These two rooms are well worth a visit in their own right, but there are also several galleries for temporary exhibitions, currently featuring an immersive and interactive installation, Subterranean Elevator (2025) by Di Mainstone, and a show of works by Philip Wilson Steer, presented ‘in conversation’ with a commissioned piece by Ben Youdan and selected works from the collection. However, with an exhibition of the Surrealist and war artist Albert Richards now on display, this is the perfect time to visit.

Richards is best known for his self-portrait The Seven Legends (1939), which hangs in the 20th-century room of the Walker Art Gallery in Liverpool. Produced while still a student at Wallasey School of Art, the painting is clearly inspired by his visit to the infamous 1938 International Surrealist Exhibition at the Walker, Richards attended the exhibition with fellow student George Wallace Jardine. In the painting, a bespectacled young man stands barefoot on a beach, holding a mouse by its tail, while a white rabbit sits in the pocket of his grey woollen suit. Surrounding the artist is a host of demons that simultaneously rise from the sea and fall from the sky. A parachutist is seen tumbling earthward as his ‘chute fails to fully deploy. A prophetic vision? Later, Richards would become a paratrooper during the D-Day landings, playing a key role in helping the Allies gain a foothold in mainland Europe.

The exhibition at the Williamson includes a selection from their extensive collection of over two hundred works by Richards, with around twenty featured here. Also on display are a self-portrait by Stanley Spencer (a major influence on Richards) and a rather bizarre painting by his close friend Jardine, Hen People Flying Kites (1985), which evidences the lasting impact of the Surrealist exhibition on both artists.

I timed my own visit to coincide with an insightful tour by the collection’s manager, Josh Mackarell, who passionately advocated for this retrospective of Richards’ legacy. Josh was well informed and offered a valuable insight into Richards’ life and work. The tours are monthly, and well worth attending. The exhibition begins with several early graphic works. Initially, Richards considered himself a designer rather than an artist, and his early book cover designs, such as H.G. Wells’ Among Stars, attest to his dynamic compositional skill, a quality that remained consistent throughout his career that significantly elevates his subject matter.

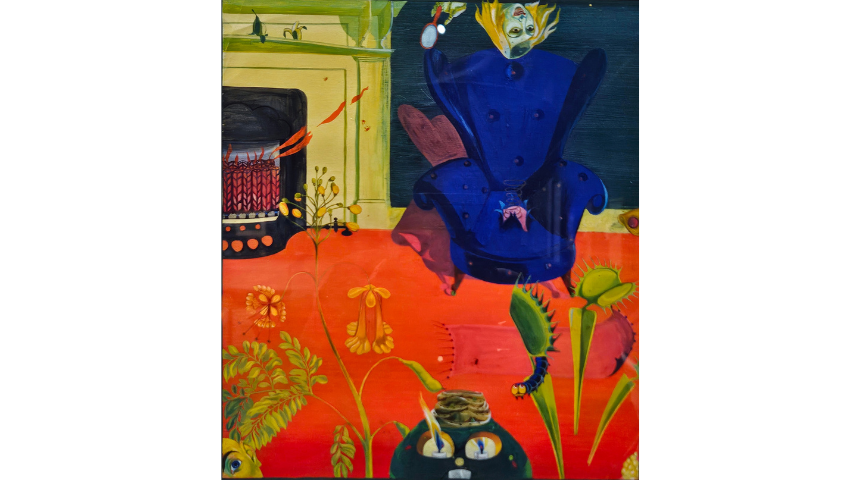

Albert Richards At Home (1938–39) gouache on paper 26cm x 23.5cm (Photo: David Hancock)

Inspired by the works of Dalí, Miró, and Ernst, Richards began to merge real and imagined elements, as seen in the standout gouache work At Home (1938–39). The painting depicts the sitting room of his parents’ house in bold primary colours. We see the armchair, the fireplace, and an assortment of houseplants. Yet, on closer inspection, the scene shifts into a suburban nightmare. A spring bursts from the centre of the vivid blue armchair, revealing a fleshy cavity. A disembodied female head floats upside down, turning away from a handheld mirror. Flames lick out of the fireplace. The bottom half of the composition is mostly taken up by a scarlet carpet, over which an insect crawls, there is a sinister assortment of exotic plants, including a Venus flytrap. It's a disconcerting image, transforming the banal lounge into something eerily alien. In this early work, Richards clearly channels Freud’s idea of the unheimlich (the unhomely) where something familiar or comforting (what could be more so than his parents’ sitting room?) suddenly shifts to become strange and unsettling.

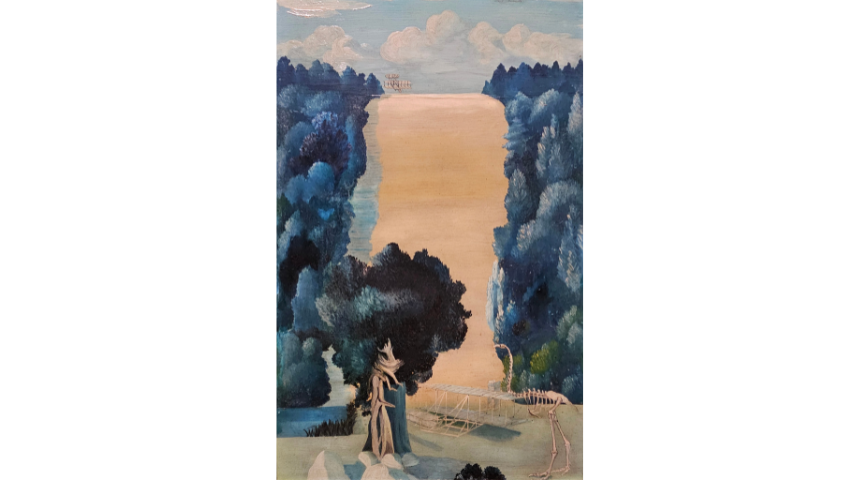

Albert Richards The Process of Time (1939) oil on board 57.7 cm x 36.6 cm (Photo: David Hancock)

Richards’ landscape paintings, one of which is included in the exhibition, are also notable. Eschewing the traditional horizontal format, he instead crops the composition vertically, elongating the image with trees framing the left and right edges, while a strip of ground rises from bottom to top. The Process of Time (1939) foregrounds a dinosaur skeleton in the lower quarter of the composition, beside an early biplane. Through the branches of a gnarled tree a small lake is glimpsed, and in the uppermost strip of sky, another biplane prepares to land. The juxtaposition of these incongruous elements reinforces the theme suggested by the work’s title, set within a bucolic landscape. Richards boldly attempts to bridge prehistory and the present, creating a surreal dialogue across a receding terrain.

Alongside Jardine, Richards was accepted at the Royal College of Art in 1939. Whilst Jardine remained at the RCA due to ill health, Richards was conscripted into the army in 1940 after only three months of study. Paul Nash and Stanley Spencer were teaching at the time and would have had a significant influence on Richards’ work. Richards enlisted as a sapper in the 286 Field Company of the Royal Engineers and was promoted to the rank of Lance Corporal. He served as a sapper from April 1940 until the middle of 1943.

Albert Richards A Searchlight Battery (1942) oil on board 50.8cm x 75.9cm On loan from the collection of Imperial War Museum (Photo: David Hancock)

As Richards entered military service, his work became less overtly surreal, depicting scenes from army life and the home front. A Searchlight Battery (1942), painted while on leave in Liverpool, acknowledges the efforts of those defending the city from relentless Luftwaffe attacks. In a letter, Richards described the work as representing “a searchlight battery on the end of a pleasure pier at the mouth of the River Mersey, an area which suffered much in the winter of 1941 from the German Bomber. Now, after a night of terror, the battery continues its ever-watchfulness.” In the scene, a gunner peers skyward, eyes alert for danger, while on a bench, a man gazes with equal intensity between the legs of his female companion. Another figure sprawls on the pier, while a guard seemingly misses an intruder shimmying across a cable to access the searchlight. Richards appears to suggest that while the gunners remain focused, others carry on regardless. It’s a humorous work, but one that also underlines the stoicism of those protecting Britain’s coasts and cities.

Richards applied several times to the War Artists’ Advisory Committee while serving as a sapper. Six works in the exhibition depict his experiences erecting Nissen huts and temporary buildings. The work was monotonous, and Richards lamented the limited daylight hours available to complete his watercolours. His frustration is evident in his comment that “the huts are not regimented into beautiful lines of threes”, which clearly hampered his ability to arrange them into a satisfying composition. Dissatisfied with the work, Richards volunteered for parachute training in 1943. Alongside Seven Legends, an earlier woodblock print, Birkenhead Ferry: A Surrealistic Study, included in the show, also features paratroopers in the sky. Richards harboured a desire to be airborne, and his decision fulfilled a lifelong passion.

Albert Richards Stone Quarry at la Delivrande (1944) watercolour and ink on paper 58.5cm x 74.2cm (Photo: David Hancock)

The final pair of paintings was produced once Richards became an official war artist and was granted an honorary commission with the rank of Captain. On D-Day, Richards landed in France by parachute with the 6th Airborne Division, disabled the gun battery at Merville, and captured the village of Le Plein. He advanced with the British Army through France and into Belgium and the Netherlands. Richards produced numerous works during this period, including France (Beach Head), The Orchard By Pass (1944), and Stone Quarry at la Delivrande (1944). These two works highlight an increased confidence in his ability. His rendering of the stone quarry feels somewhat akin to Ernst’s use of decalcomania in works such as Europe After the Rain II (1940 to 1942) and The Eye of Silence (1943 to 1944), achieved using only ink and watercolour. The limited palette of earth tones perfectly conveys the dusty scene as American troops load a truck with gravel for road repairs to aid the advance. Similarly, his sparing use of wash and line to depict trees laden with fruit in The Orchard is also rather unique, and the painting appears to be rendered using a camouflage technique. Richards’ deliberate restraint in the use of colour encourages the viewer to reconstruct the vibrancy suggested by form and texture, while the presence of soldiers at work reinforces its documentary intent. Richards was provided with his own jeep to travel and collect material for his paintings. On 5 March 1945, Richards was killed when his jeep struck a landmine. He was 25 years old. He is buried at Milsbeek War Cemetery, near Gennep.

Albert Richards France (Beach Head), The Orchard By Pass (1944) watercolour and ink on paper 53cm x 72.7cm (Photo: David Hancock)

This retrospective at the Williamson Art Gallery offers a poignant glimpse into the short but extraordinarily rich career of Albert Richards. Moving from surreal imaginings to the stark realities of war, the exhibition charts not only his evolution as an artist, but also the personal journey of a young man whose creativity remained undimmed even amidst the chaos of conflict. Thoughtfully curated and deeply affecting, drawing on and showing materials from his family archive, the show is a fitting tribute to a compelling yet underappreciated war artist. Albert Richards at the Williamson Art Gallery is a timely reminder of the power of art to both reflect and endure in the face of destruction.