FEATURE Oct 2025 Shining out ‘From the Shadow’ – Ten Obstructions at Rogue

Jo Manby

Jane Fairhurst Fetishes for Uncertain Times (2019-2023) Dimensions vary: Tallest with textile 125cm, shortest with textile 95cm Photo: Matylda Augustynek

Commanding the first floor space of Rogue Artists’ Studios CIC, a presentation of vibrant and eclectic two- and three-dimensional works of art formed the exhibition ‘From the Shadow – Investigations by Ten Obstructions’, bathed in the room’s pale yellow light, where artist group Ten Obstructions exhibited work of an order that distributes power and agency. ‘From the Shadow’ took its title from a line from Auden’s poem, As I Walked Out One Evening, and was held as part of Rogue Artists’ Studios CIC 30th Anniversary celebration running from 6 to 28 September 2025. the Fourdrinier editor Jo Manby spoke to Christopher Rainham about the show and reviews it here.

The 2011 film The Best Exotic Marigold Hotel, filmed mainly in Rajasthan, India and with a stellar cast, took as its central theme the idea of focusing on the lives of the elderly beyond standard expectations of their age group, and on a particular group of seven older people coming together to outsource their retirement in warmer climes. Ten Obstructions is a group of ten artists, initially convened as the first cohort of Castlefield Gallery’s 2019 talent development project for artists over 50, the bOlder programme, part of the GMCA’s Age-Friendly Cities initiative. Eight of them are exhibiting in ‘From the Shadow’, and far from heading quietly into the late stages of their careers, they are all working hard to produce art that is increasingly exciting, engaging and complex, and continue to support and nurture each other’s practices in what has proved to be an informal, mutually beneficial collective.

Christopher Rainham, who meets me in ‘From the Shadow’ at Rogue Artists’ Studios to discuss the show, cites the inspiration of Liz Lerman’s Critical Response Process in describing the original formation of Ten Obstructions. He explains that Lerman designed a way of generating very structured group crits using a prompt sheet, which would be used by participants. They would look at the work presented and then respond in several predetermined ways. ‘”What do you see?” is asked,’ Rainham says, ‘inviting no emotion but simply a basic description. Then further questions can be asked: “Do you want people to respond?”, “Do you think it is finished?” Then there are the more permissive questions, “Can I ask you about your process?”’

Rainham tells me it was Matthew Pendergast, Head of Programmes at Castlefield who came up with the obstructions idea as a method of diverting the bOlder artists’ practices, inspired by the film Five Obstructions by Lars Von Trier and Jorgen Leth and the origin of their collective name. Castlefield were running the Salford School of Art and Manchester Metropolitan University Graduate Scheme and paired up the graduates with members of bOlder. Ian Vines, who tends to work from an archive of objects he has at home, was instructed: ‘You cannot use any stock materials or photos.’ Then graduate Parham Ghalamdar gave Rainham a sheet of instructions that included, ‘use oil’, ‘be inspired by Caravaggio’. ‘There were six instructions,’ Rainham recalls, ‘but each had subdivisions so there was quite a lot of detail – “use a bigger brush”. The idea of obstructions was also inspired by the Eno/Schmidt Oblique Strategies card deck, subtitled ‘Over One Hundred Worthwhile Dilemmas’, a method for promoting creativity jointly created by musician/artist Brian Eno and multimedia artist Peter Schmidt, first published in 1975. Each card presents a challenge intended to help artists break a creative block by encouraging lateral thinking.

Jane Fairhurst Fetishes for Uncertain Times (2019-2023) Dimensions vary: Tallest with textile 125cm, shortest with textile 95cm Photo: Christopher Rainham

Immediately striking the viewer on entering ‘From the Shadow’ was the work of Jane Fairhurst. Fairhurst has worked from her studio at Cross Street Arts, Wigan, of which she is a founding member, for over twenty years. She studied at Liverpool College of Art and returned in 2010 gaining an MFA with distinction. She exhibits nationally and internationally and is represented by Saul Hay Fine Art, Manchester. In ‘From the Shadow’, Fairhurst exhibits Fetishes for Uncertain Times and The Distaff Side 2019-2023. These striking textile sculptures were created ‘in response to unsettling global politics, increasing climate change and war.’

Sewn out of clashing patterned fabrics, where a turquoise and orange daisy print sits adjacent to a white on green polka dot, with a row of five nazar eyes or a patch of multicoloured buttons fixed with red thread, as Fairhurst explains, ‘they are a result of my in-depth research into ancient protective devises, amulets, talismans and fetish objects… I created my own objects of agency that challenge form and function in a shifting world where old certainties are no longer in place.’ Fairhurst employs ‘an “amuletic code”, using asymmetrical pieces of plain and gaudy fabric with hand-sewn decorations in the form of shiny objects… with embroidered dots, webs and wavy lines using traditional craft skills handed down through generations of women.’

Rather than rely on traditional plinths, Fairhurst designed metal stands and commissioned a local blacksmith to fabricate them. ‘Later, when I made the smaller textiles, I designed metal plinths in the shape of distaffs, tools used in weaving that relate to women’s long connection with the production of cloth. Again, commissioned from a local smith.’ By combining her own work with found textiles gathered from her travels in Turkey and North Africa, Fairhurst has created a spellbinding installation that bristles with archaic energies and intercultural wisdom, a blockade to counter menacing forces at work in our times and an opposition to future destruction.

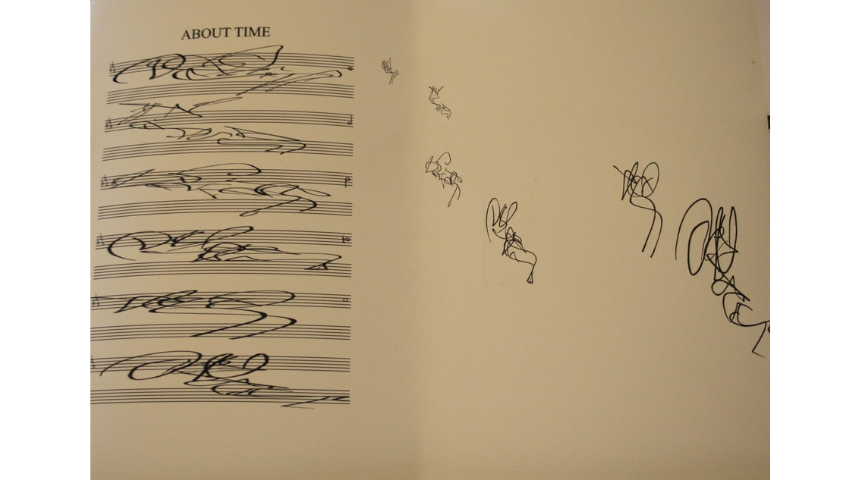

Paddy O Donnell About Time (2025) mixed media courtesy the artist Photo Christopher Rainham

While still practising as a lawyer, Paddy O’Donnell went to an atelier art school, to learn the basics of traditional sculpture. In 2022, during a period of self-doubt, he visited a live jazz session and remembered how, at school he used to execute quick-fire drawings. He now has a studio at AWOL, Manchester. O’Donnell exhibits About Time (2025) an abstracted series of six lightning sketches of a saxophonist, Alex Clarke, in performance at a jazz club in Stockport rendered as sheet music. I ask O’Donnell about a painting on a wall in a Stockport jazz venue that Christopher mentioned. ‘This is The Pineapple, an old-fashioned boozer in Edgeley… I love to get my work into the ‘real’ world and this was available on my doorstep, with practically empty walls and a receptive landlord. I started by putting prints of my work into the bar (I had done something similar in a night club in Leeds the year previously). Then I turned my attention to a semi-derelict room at the back,’ O’Donnell explains. ‘Made a sort of collage of some of my sketches on the walls. Then I added colour, in parts - though I have no wish completely to change the space, preferring to work with it. Sometimes (to the annoyance of the landlord) customers add to my drawings. Sometimes, I cover these additions. Other times, I leave them. This space leads to the loos and beer garden, where they smoke. So, there is a constant flow of customers, mostly elderly. Often, they stop to chat, and ask about, or comment on, the images. Every so often the landlord offers me a drink. It’s quite sociable.’

I wondered whether O’Donnell has a method of ‘getting in the zone’ with his quick sketches of Jazz musicians. ‘I don’t wait to get in the zone. I listen for a few minutes, then make a sketch or two. Often, I don’t feel like it. But feeling like it doesn’t seem to make any difference. Each sketch is done in a matter of seconds. I don’t try to draw well. I even sometimes, try to draw as ‘badly’ as possible. Occasionally, I get a likeness of a musician. But I’m more interested in the energy I just draw, and keep drawing - often 20 or thirty sketches in a night.’

Christopher Rainham Crumbs of Shadow (2024) acrylic on canvas 60 cm x 60 cm courtesy the artist Photo Christopher Rainham

Christopher Rainham graduated from Wolverhampton Polytechnic with a degree in Fine Art in 1989 and works from his studio in Hebden Bridge and is represented by Comme Ca Art, Manchester. His paintings employ acrylic paint thinned to a glaze with water, conte and colour pencils and sometimes text, often to depict birds and other aspects of the natural world in sensitively attuned rainbow hues and bold, broad brushstrokes underpinned by precise drawing. The accompanying anecdotes and folklore are an interesting addition and something that Rainham has not presented previously. ‘I tried to write them like the sort of conversation I would have during an open studio or opening of an exhibition, when you have an opportunity to respond to someone looking at the work,’ Rainham explains. ‘The majority of the things I make go to art fairs or commercial galleries where the engagement with an audience is almost exclusively from the appearance of each painting. The paintings and drawings have to work like this, with some help from the gallerist, but I find it frustrating that the wider inspiration or motivation is often missing. Lots of starting points for work get discarded during the process of making but I would still find them relevant to the works genesis.’

I asked Rainham how much agency he thought art had to counter some of the negative aspects of the era we are living through. ‘I think it is highly unlikely that a painting, book, poem, song or ballet is going to stop what is happening in the U.S.A. or the Middle East,’ he said. ‘Historically art has usually been at the heart of these things only to record or comment, to bear witness. There seems to me to be very little protest in culture at the moment, I don’t think K-Pop will spawn a new Dylan or a Bowie… if there is a political or social aspect to my practice it is in saying “these are the things I have come to know about the natural world and if you knew about them it might change some of your habits or ideas”. I live a dilemma in that I create luxury items that I need to sell to continue to practice but hate consumerism, the art market and the waste of the Earth’s resources.’

Tina Finch Kiss Within the Shadow (2025) (1 of 3) acrylic on paper 38 cm x 31 cm. image courtesy of Tina Finch

Tina Finch recently completed an MA at Bolton which offered not only academic structure but also the space to question, dismantle, and reimagine ways of working. Finch is a Gallery Associate of Castlefield Gallery, Wigan Art Space, Cross Street Arts in Standish, and Saatchi Online. Finch displays a triptych painted in richly layered acrylic paint exploring the shifting topography of memory through a timelapse effect. ‘Each panel reflects a stage in the process: first fragmentation, then gradual gathering, and finally a deeper settling, where shadow and form crystallise into a more embodied image. The final convergence reflects the way memory solidifies into lived experience.’ Finch is interested in what emotional and spiritual essences can be summoned by manipulating the materiality of paint through gestural abstraction, relishing its ‘viscosity, resistance, fluidity and unpredictability’. A repeated green ground runs throughout the triptych, a colour she uses to evoke both growth and renewal, and secrecy and foreboding. ‘In this sense,’ Finch explains, ‘green becomes a threshold — a zone of passage where presence drifts into absence, and the familiar dissolves into the unknown.’ From this ambiguous painterly landscape emerge ghostly, luminous figures – flashes of clarity or innocence set against darker, more turbulent grounds. They evoke the fragile spirit of an embrace, a moment of vulnerability, or a memory retrieved from the deep forest of the past or from the subconscious.

Sabrina Fuller Now Is the Time (2025) mixed media courtesy the artist Photo Christopher Rainham

Sabrina Susan Fuller uses still and moving image, voice, sound and the written word. Collective and collaborative working has always been fundamental to her practice: as well as Ten Obstructions she is part of Deluxe film-makers collective and Feminist Duration Reading Group. Now is the Time could be read as a narrative. There is a protagonist, but what’s the story? Is it for the audience to wander through and ponder? Is it an archive of evidence of the process of memory? I asked Fuller what media and processes she had used and she described layering ‘digital photographs and monoprints printed on paper and transparencies; text (from Woolf’s To the Lighthouse) on tracing paper; embroidery on muslin, and cassette tape. The elements are… suspended by fishing wire and bulldog clips to produce blurrings, repetitions and superimpositions.’ The work is based on an idea that time only exists within ourselves, ‘suspended between memory and anticipation. The work explores the nature of memory and our perception of time, as partial, contingent, subject to influence, recurrence, distortion and failure.’ As a key influence, Fuller cites Carlo Rovelli’s The Order of Time (2017), which ‘proposes that our concept of linear time is an illusion based on selective perception. Recognising the different layers and weavings of temporal strands enables a critique of the political control and power dynamics intrinsic to a straightforward past-present-future chronology.’ Fuller’s work is compelling and mysterious, like the evidence board of a half-remembered dream, where traces and residues of things past or hovering in the future de- and re-materialise.

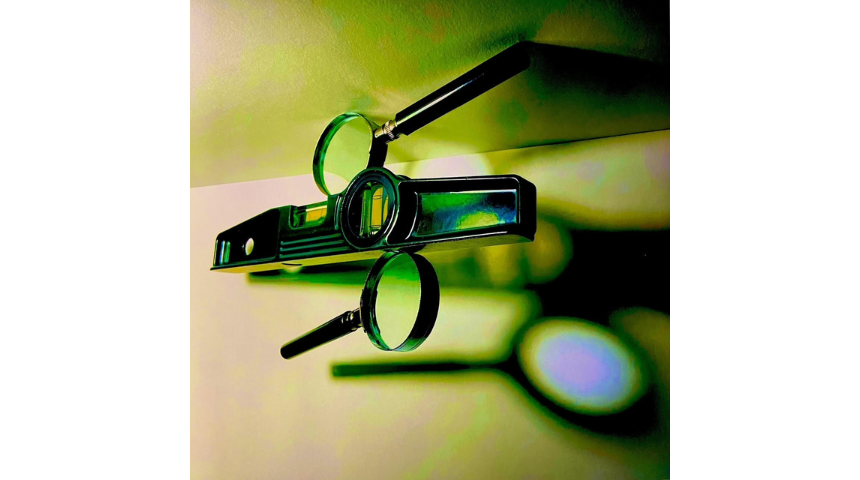

Ian Vines object and image (2025) digital photograph 30.5 cm x 30 .5 cm courtesy the artist Photo Ian Vines

After studying fine art, Ian Vines worked in galleries and museums, devising and organizing exhibitions, residencies and commissions. Previously a curator at Stoke-on-Trent museums, he uses a range of physical objects in his installation in ‘From the Shadow’, which he lists for me as follows: ‘digital photographs, which often incorporate enamel paint and collaged material, spirit levels, magnifying glasses, a mirrored bowl, mirrored plates and enamel paint, metal discs and a painted wooden ball suggesting a heavy lead ball, plus assorted elements, including an old hinge, brackets, a metal rod, wire and string.’ The work is very compelling and satisfying, and I wondered if it generates this kind of feeling in Vines when he completes a work (or indeed is in process of making a work). ‘In developing the work, which is often a matter of trial and error, I try and get the different elements to work together in a harmonious way, but also create an intriguing situation which raises questions about relationships between objects and images, shadows and reflections. The intention with all the works is to engage the spectator in the processes and complexities of looking, but often in quite a playful way.’ I asked how he plans his colour harmonies, or if is it more improvised than planned. ‘The starting point for the colour harmonies are usually the objects and materials. One of the spirit levels is green and the glass of the magnifying glasses often throws greenish tints. I often play with the colours, emphasising or enhancing various effects… In the installation, the predominant colours and optical effects are greens, blacks and the various reflective surfaces, which hopefully ties things together, while providing contrasts between the different elements.’

Claire Hignett To Twotoo: Threaded Dance (2025) mixed media 65 x 61cm courtesy the artist Photo Christopher Rainham

Claire Hignett is an artist with an extensive knowledge of textile processes. In 2015, having picked up fragmented arts education at night school, she joined Islington Mill Art Academy – a peer led experiment into alternative art. I followed Hignett on Instagram in lockdown when she found a hoard of abandoned knitting machines. She was trying to depict a cartoon character’s emotions in knitting. I was fascinated to understand if there was something in the challenge and the difficulty level of executing work like that that enhances the meaning and development of the work for her. ‘The knitted work around the cartoon character was part of DYCP funding in September 2021 – Emotional Inheritance and the knitting machine. This was to bring my knitting machine skills back up to scratch and to develop them further and to create textures that create an emotional response at a preverbal level,’ Hignett explains. ‘Basically, I would use the story of Thumbelina, as told in my childhood picture book, published in 1965 and with illustrations by Giovetti, [which] I felt captured her emotions really well, particularly to a small child. I realised it was the position of her eyebrows that showed how she was feeling, scared and alone, wary etc. I used the eye brow positions to create knitted textures, and to do this had to learn new machine knitting techniques.’

I wondered whether there was something about so-called women’s work of stitching and sewing and the combination of contemplation and sociability in that that attracts Hignett to working with these media. ‘I embroider/stitch by hand and make fabrics using the manual domestic knitting machine. Both comprise straight lines and loops, both involve brain/hand co-ordination/communication… both deeply meditative… I also feel there is something about the huge amount of time it takes to make that symbolises care, which is an important element of my work around safe, unsafe and wary.’

Hignett also tells me how, like many women, ‘women’s work’ is in her creative DNA, whether she wants it to be or not. ‘I was taught to embroider by my Grandma, born a Victorian – to knit by my Mum born in the 1930’s and to patchwork by a woman down our street, and then went to a school at the tail end of the period when girls weren’t allowed to do woodwork and metalwork. I think if I’d gone to University and studied art I would have been a sculptor… I have sometimes wondered about changing medium,’ she adds, ‘but I have such an in-depth knowledge of textiles, structures and techniques, I could never get that mastery without a long period of study, so wouldn’t be able to make work with real depth for a long time.’

Sarah Feinmann From the Spiral Ramp (2025) painted collage courtesy the artist Photo Sarah Feinmann

Sarah Feinmann studied B.A. (Hons) Fine Art Manchester Polytechnic 1978-1981 and completed an MA in Fine Art (Projects for Places) UCLan Preston in 2020. Here, she exhibits ten small works grouped together as From the Spiral Ramp (2025) in painted mixed media collage. Fleeting glimpses captured from the window of a vehicle circling down a ramp inside a Brutalist carpark give a sense of completeness despite the fact that they are fragments of a wider scene. These are the views that the artist wished to depict. But the grouping is also expansive; the artist could add to the collection or they could be isolated and stand alone. The palette is urban, gritty, autumnal. There are chestnut browns, slate grey, olive green, sage, emerald, ochre and cream. Rhythms and internal visual rhymes resound within the set of works – the upcurve of a ramp, the loop of a handrail, the slant of a centrifugal concrete structure.

I wondered if Feinmann practiced setting herself an obstruction puzzle and if this was helpful in developing her practice. ‘I’ve found each exhibition challenging—often unsure how to respond to a title or theme—but this uncertainty has been productive… allowing me to explore different disciplines and processes that I naturally gravitate towards.’ With previous Ten Obstructions exhibitions, each one was a new challenge, although underlying methods and materials often remain the same, ‘forming a continuous thread through my practice.’ Feinmann describes the work she made for the exhibition ‘Gladly Beyond’ as emerging from a desire to explore the subdued colour of the ‘edgelands and overlooked spaces—areas that have always intrigued me. It began with fragments of paper, then large painted sections of colour, which I cut up and collaged together.’

In From the Spiral Ramp, Feinmann combines her preferred collaging method with painting. ‘For the first time I knew exactly what I wanted to do for ‘From the Shadow’ and how I wanted to develop the spiral ramp pieces. Although these works feel like new departures, they are still connected by an underlying continuity in theme and material. I’ve come to realise that while I enjoy working with these “obstructions,” I also welcome the creative challenge they present—and the way they push my work forward, often in unexpected and rewarding directions.’

Using Instagram as an exhibiting platform was the first obstruction the group had to contend with. This was organized during the Pandemic in 2020 and was followed by ‘Obstructions’ at Castlefield Gallery and ‘From the Ground Up’ at Castlefield Gallery’s New Art Space Wigan in 2021 and ‘Through the Looking Glass’ at The World of Glass St Helens in 2022. ‘In the Making’ was exhibited at Salford Museum & Art Gallery and ‘A Cabinet of Curiosities’ at Dez Rez Project Space on Manchester Deansgate in 2023, and in 2024 ‘Gladly Beyond’ at Rogue Artists’ Studios CIC. ‘From the Shadow – Investigations by Ten Obstructions’ is their latest exhibition, and with such a wealth of compelling, challenging and inspiring work, audiences can look forward to many more such productive showings from the group as the early decades of the 21st century unfold.