REVIEW Jul 2025 ‘Expanding Landscapes: Painting after Land Art’ at Abbot Hall

Kirsty Jukes

Expanding Landscapes install shot, Ingrid Pollard and Jessica Warboys

Art historian and writer Kirsty Jukes reviews ‘Expanding Landscapes: Painting after Land Art’ at Abbot Hall, Kendal. Co-curated by Rebecca Partridge and Joy Sleeman in collaboration with Helen Stalker, this exhibition follows the elemental motifs of earth, sea and sky through a variety of materials and processes including the use of earth pigment from specific locations. Giving viewers a chance to consider work from the emerging 1960s Land Art movement in dialogue with contemporary artists, the show explores the importance or insignificance of humanities interaction with the land around us. ‘Expanding Landscapes: Painting after Land Art’ is on view until Saturday 6 September 2025.

Now in the shade he loves to lie

Under the ancient Oak

And now upon the verdant grass

Beneath th'o'erhanging rock

Meanwhile the dashing waters fall

Birds in the forest sing

The little streamlets murmuring flow

All which sweet slumbers bring.

Sara Coleridge, ‘Praises of a Country Life’

A verdant green undulates steadily on a flickering screen. Through grainy footage, subtle movements under grass suggest the Earth is respiring like a lush lawn lung rising and falling. A brief gasp, then a lull. Ana Mendieta’s Grass Breathing (1974), stood out to me as a key example of Abbot Hall’s ‘Expanding Landscapes: Painting after Land Art’ exhibition theme. Despite the fact that it isn’t actually a painting, there are a number of video pieces around the gallery space, and this is one of two artworks on display here by the innovative Cuban-American artist highlighting the interchangeability of language, links between humans and nature all through the emergence of a timely artistic movement.

Land art countered sublime Romantic ideals prominent in the landscapes of J.M.W. Turner, Constable and their contemporaries with a call to use intellect alongside emotion when interacting with our environment. Rejecting suggestions that nature is a place of fleeting, grandiose escapism to be conquered, their work instead focused on the vulnerability of physical experience in the landscape, not merely as an observer but also as a participant. They changed attitudes towards working with and on the land, questioning the reality of who gets to access green space for work and play. During the Golden Age of Capitalism, artists from the movement drew attention to the cause and effect of humanity’s encroachment on the landscape by challenging traditional notions of art as a commodity via interrogative and environmentally conscious work. Land art is a contested term as no manifesto exists and the challenging viewpoints of its artists allow an opportunity for open-ended discourse made more difficult in proscriptive art movements. When staring at the uncanny surrealism of Mendieta’s Super-8 student film, all of these issues swirl around my mind.

Under earth is where many of us return when our lives are over. Here we break down to feed the soil so that others may live after us. This process is part of a complex eco-system, each element of which relies on the other. Life and death are circular, our own ouroboros. Ex-bodies provide key minerals vital to the health and expansion of many species. In life, we breathe that which the Earth creates through carbon cycles, photosynthesis, solar energy, chemical energy, cellular respiration – a breath for a breath. In Mendieta’s work, she translates the invisible stomata gas exchange, or ‘breathing’, of trees, plants and grasses into a visual, bodily process. Mendieta is excellent at highlighting finite and infinite parts of humanity and our place in cycles that existed before and will remain long after we are gone. A deep, spiritual link to her environment and body is present in much of her work . Using ecofeminism as an idea through which to explore displacement, ancient ritual and the universal, she created a unique visual language encouraging a return to the land that was both gentle and violent in equal measure. Her untimely death at age 37 only adds to the poignancy of this work. She is buried at Cedar Memorial Park, Cedar Rapids, Iowa, perhaps not too far from where she shot this footage; feeding the very grass she gave artistic life to, still breathing with us, living on in an eternal exchange with her viewers. Breathing Grass acts as premonition, a permanent memorial of her vivacity and continued presence, proof of life.

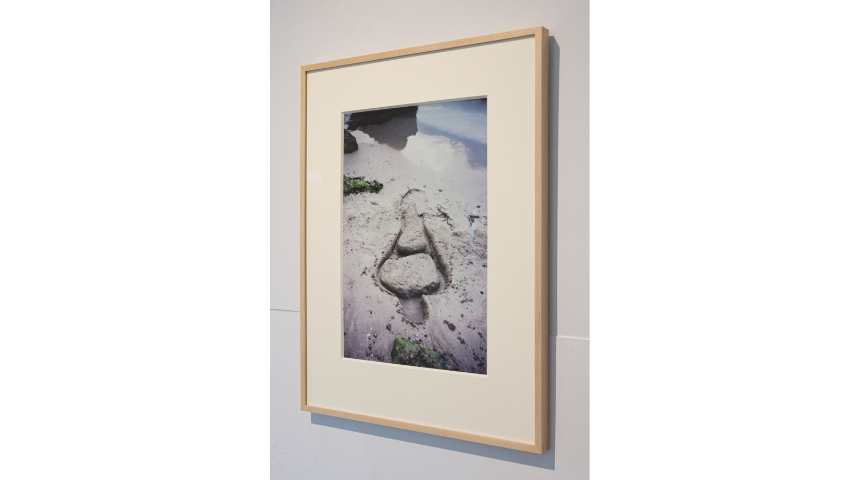

Ana Mendieta Untitled (1981) colour photograph edition of 10

Unstoppable even in death, women are a life force even when their lives are taken from them. We contain that which is essential and encapsulate the value of growth over destruction, life over death. A constant feminine power is evident throughout this exhibition in which the curators Rebecca Partridge, Joy Sleeman and Helen Stalker have clearly done the work in ensuring what can be seen is weighted heavily towards women's experience of their surroundings. To my mind, there is something innately feminine about slowing down to appreciate the small details; the particles and fragments of life that hold sway on so much power. That this exhibition is in the Lake District is key, especially when understanding the importance of the landscapes surrounding Abbot Hall in many areas of art history. Kurt Schwitters, John Ruskin, Josefina de Vasconcellos, Hilde Goldschmidt and Sheila Fell are just a few of the visual artists who were inspired by Cumbria’s outstanding natural beauty. During the time Land Art was coming into being, the art world was more keenly focused on art of the self. Pop Art, Performance Art, Graphic Expressionism, portrait photography and the Young British Artists (YBAs) were all considered avant-garde. Landscape art however remained the quiet, uncool cousin of these art world behemoths for some time. It is exciting to me that, at this crucial point in our climate change trajectory, ‘Expanding Landscapes’ gives space to this important movement away from any distractions.

Reminders of our collective insignificance are all around the space in work that frames our particular moment in millennia of history. Ingrid Pollard’s Landscape Trauma series (2005) are eight tinted black & white photographs printed on Japanese paper. Like floating inks of marbled Suminagashi or the swirling, stormy surface of gas giant Jupiter, Pollard explores ideas of chemistry, physics, and the basic constituents of photography whilst expressing how, through alchemy, the physical world around us is captured (2). These geological patterns seem fluid, uncertain, and this speaks to the time in which they were created. At the turn of the millennium, unsettling social, cultural and political events were commonplace. Pollard tried to make sense of this through creating a freeze-frame from which to step back and observe. With the distance of time, I find a somewhat hopeful message amongst the maelstrom in trusting my anthropocentric existence to the celestial mechanics of deep time.

Expanding Landscapes install shot, Roger Ackling One Hour Sun Drawing (1978) and Nancy Holt's 1978 film Sun Tunnels

In another room, Katie Paterson’s O series pinpoints materials sourced from across the cosmos in primal, minimalist works. Her pigments are made from pre-solar dust, fossilised cellular life and minerals from prehistoric seas and the Earth’s strata. This hyperfocus is used to dazzling effect here with viewers coming face to face with glinting prehistory, a wink across time. Pigments from the landscape are employed to full effect by a number of other artists too. Tanoa Sasraku’s Red Gate (Terratype) (2022) is a rich, layered piece soaked in sediment. Her organic forms are portals to the primordial with a side of Modernism. Onya McCausland’s four site-specific co-ordinate works are made in collaboration with local industrial areas. Deep ochres saturate each square and remind me of Halima Cassell’s practice of unifying communities through shared history of the land. Jessica Warboys River Painting, Ouse (2019) is a vast, abstract work of performative action in the landscape. Using the rhythms of rushing water to create Expressionistic textures, the artist allows chance acts of staining and removal to reveal a narrative.

There are parts of the exhibition that focus on wildness in urban places, a particular area of Land Art I am drawn to. When I was living in cities during most of my adult life, I sorely missed the wide open spaces of Lancashire glimpsed through the windows of vehicles on drives or commutes. Early 1960s concrete modernism present in my childhood hometown of Skelmersdale was full of these tiny patches of vegetation, rudely interrupting the brutalism that surrounded me with bright greens, oranges, purples and reds. Those tears in the fabric of grey suburbia through which budding life can be glimpsed are so beautiful to me, as nature rebels against our attempts to control it, making soft our hard-edged constructions.

Rebecca Partridge Wildflowers, Night Lace (II) (2023) oil on panel

In particular, the works of Hannah Brown and Rebecca Partridge tightly focus on the plant life to be found in garden hedgerows and overgrown plots. Brown’s The Verge by James Lane 5 (2024) speaks directly to the weighted legacy of British landscape traditions whilst simultaneously offering a contemporary view of what green space now represents in this country. Overlooked, liminal areas in places experiencing economic decline are all too recognisable; I find seeing them painted large on canvas both comforting and disturbing, a common postcard from home. In her own words, she looks for “quiet, potentially unsettling places with a peculiar kind of beauty”, and there is a certain level of trepidation to be felt looking into an unknowable knot of branches and vines threatening to pull you in and not let go. Similarly, Partridge’s Wildflowers, Night: Lace (II) (2023) displays a similar interest in romantic decay and psychological immersion. Titled descriptively rather than site-specifically, there is something dystopian about her tangled carpet of stems, blooms and seed heads, almost like a matted rug laid down to ‘make house’ in a new world after we humans are all gone. Unlike art historical views of wildflowers that are often shown as pretty, cut-to-size sprays or neatly framed verges, this version denies control, strangling and obfuscating with claustrophobic, terrible charm.

‘Expanding Landscapes’ hits on two major points for me: it demonstrates the insignificance of our existence through the stretching and curtailing of time whilst simultaneously reminding of our importance by means of cause and effect. Landscape trauma that our species can and does inflict is shown on a broad scale, even when humans are absent from the frame, the threat they pose lingers on (2). Farming, urban expansion, industrialisation and war mongering all have a massive effect on the landscape as well as human populations. Every year we experience rising temperatures whilst using up more natural resources to fund our fast lifestyles and a series of seemingly never-ending conflicts. A shift into caring more deeply about preserving the beauty of our natural world and taking direct action to ensure this means our survival. Artists concerned with these issues continue to be key in developing our understanding in ways that science often cannot reach. Lakeland Arts continue in their run of creating thought-provoking exhibitions which focus on the key concerns of our time.

‘Expanding Landscapes: Painting after Land Art’ runs until Saturday 6 September 2025 at Abbot Hall.

Entry included with house admission. Pre book tickets online at lakelandarts.org.uk.

Footnotes

Expanding Landscapes preview shot, courtesy Abbot Hall

This review is supported by Lakeland Arts