Lisa Wilkens: In Conversation

by Sara Jaspan

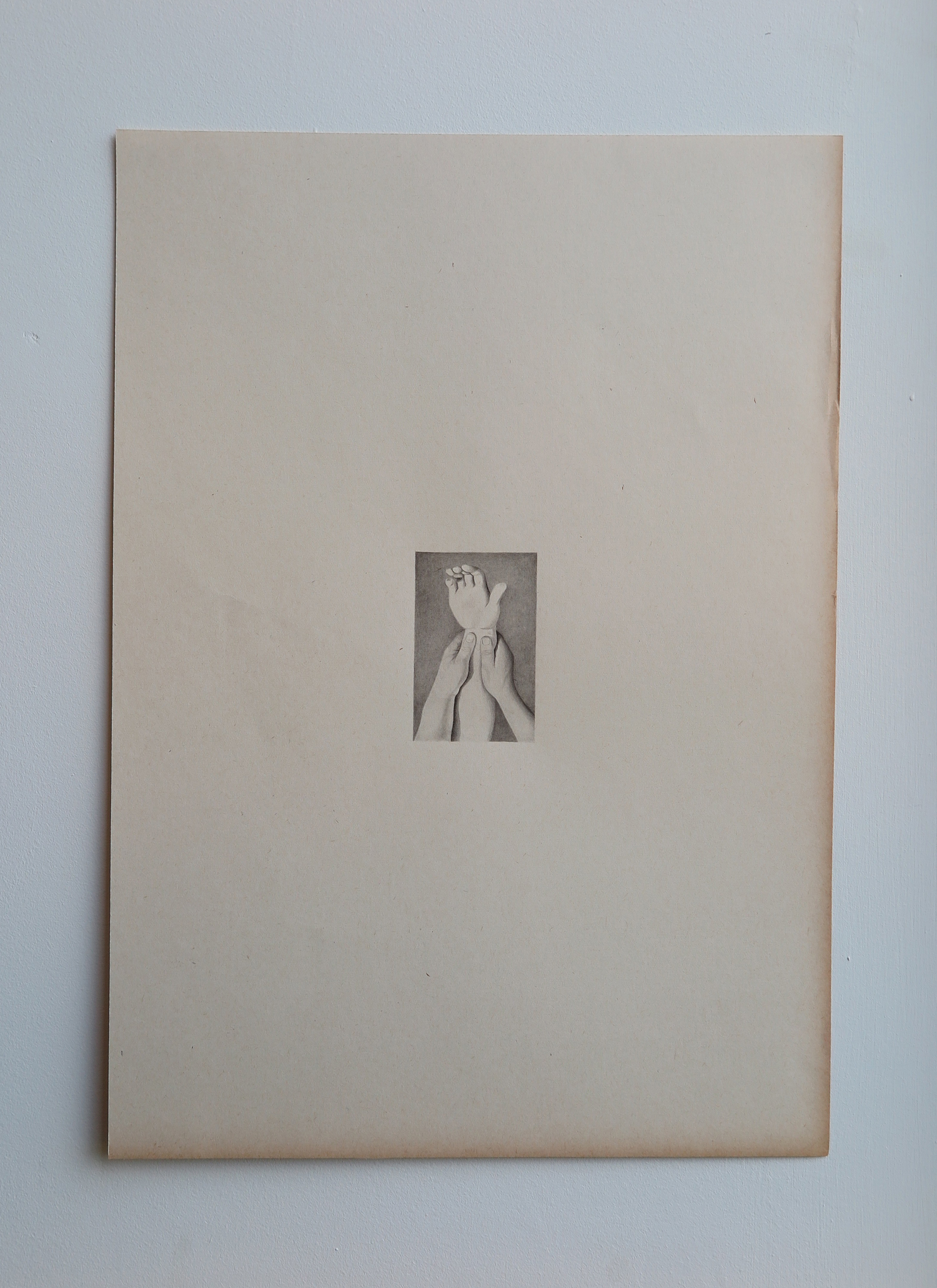

Placed at the centre of comparatively vast, yellowing borders sit the densely compact, hyper-realistic drawings of Berlin-born artist Lisa Wilkens (b.1978), currently studying at the HISK in Ghent, Belgium. Using her brush and blot of Chinese ink as an epistemic tool, within each work she sets out to explore the wealth of detailed information contained within the dated photographs she painstakingly replicates, mining them for all that can’t be gained in the fleeting glance we often pay. Her intense looking also overflows each picture’s four walls, spilling out into a wider realm of questions around the conditions under which it was produced and the society to which it belongs. Here we invited her to turn an equally intense gaze upon her practice itself, resulting in a conversation that traverses art, politics, the NHS, UBI and science-fiction.

Sara Jaspan: Your practice is quite technical whilst also dealing with some big political themes. Could you give us a quick introduction to your work?

Lisa Wilkens: I’m really interested in the notion of process and production. How knowledge of how something was produced can inform our understanding of why it was produced, the intention of the producer, and why we are seeing it.

This focus is largely informed by my educational background. I first started off studying biology at university with dreams of becoming a marine biologist, however you also needed a grasp of chemistry and physics which quickly put an end to that. Over time I gradually became less interested in the science, and more in the drawing – which you had to do a lot of as a tool for observing, describing and understanding the things we studied. About two years in, I discovered there was a degree in Switzerland fully dedicated to scientific illustration and decided to switch.

It was a drastic change. The course was highly technical – we spent the first six months learning how to draw a cube! (a training in perspective) and rendering images in just light and dark using Chinese ink. After a time though, you really start perceiving very consciously and develop a refined understanding of what bits of visual information are important in order to translate what you see on to the page and how.

A lot of what my work currently deals with relates back to these fundamentals of image-making; using the skills I learnt to look closely at photographs and convert them into drawings. Introducing a manual element into the process of observation and perception somehow adds something more to the information an image holds, and I find that really interesting.

My practice is also deeply affected by my upbringing in West Berlin during the 1970s. My dad was a member of the Marxist-Leninist party, and my mum was also involved. A lot of the stuff society is dealing with now actually feels very connected to that time. I think we’re once again at a point where it feels like something needs to change or happen. There’s a sense that we can’t go on like this anymore, and maybe a better world is possible.

Lisa Wilkens - Why Work? Chinese Ink on Found Paper (2017)

SJ: Are you talking about what’s going on in Europe at the moment? A growing separatism and nationalism?

LW: Yes, very much. I’ve read two really important books recently. One I think only exists in German so far, but its title translates as ‘Zone of Transition’ by Boris Buden; the other is Requiem for Communism by Charity Scribner. Both talk about how the fall of the Berlin Wall and the end of communism in that sense led to the complete take-over of capitalism and the erosion of the idea of society, the welfare state and any feeling of belonging, connection or shared experience. It relates back to Margret Thatcher’s claim: “There is no such thing as a society. There are individual men and women and there are families.” That’s it – no wider sense of community. I think we’re feeling the effects of that now; 30 years on.

I still remember certain aspects of living in a welfare state as a child and the more societal context or feeling it bred. But this seems unimaginable to younger generations today.

SJ: Do you mean because it’s not a part of their lived history?

LW: Yes. When I speak to some of my younger colleagues here at the HISK they simply have no understanding or reference point when I mention the idea of social housing or state-owned public utilities, for example. Their only experience is of living in a society where it’s every man or woman for themselves. The fact that things were very different not so long ago seems almost unimaginable for them.

SJ: In the UK I feel like there’s still a very strong memory or idea of ‘how things used to be’ and what we’ve lost through the reduction of the welfare state. In fact, it’s actually the younger generations who seem to feel most strongly about the need to recover some of those older, more social values.

LW: You’re right. I think it’s quite different in the UK because you still have the NHS, which is something really unique. In Germany you have to pay quite a lot for health insurance.

All the work I make is connected to how I perceive what’s going on today through the context of my own memories and upbringing, as well as the historic events I’ve lived through. But during the two years I’ve spent at the HISK, I’ve found there’s a real fear, especially among curators, of anything that could appear to be nostalgic.

For me, there’s nothing negative about nostalgia. It’s not good or bad; it simply exists and is something we all need in a way. Yet even simply using old materials (I work with a type of time-aged paper produced in the German Democratic Republic during the 1960/70s, sourced through family connections) seems to trigger alarm bells in people – like “do you just want ‘the good old times’ back?”

SJ: I think the important thing is how artists deal with or use nostalgia, and whether it has a wider, universal relevance or connection to the present. The problem comes when you’re indulging in your own warm memories, whilst offering nothing to your audience.

LW: I think I’m actually quite interested in exactly that warm feeling nostalgia generates as a thing in itself. Why does the fact that it makes us feel good exclude it from contemporary art? There’s a real value to finding a space in which you can feel at home, and if that space is located in the past then that’s ok. Obviously there needs to be something for the audience to make a connection as well; to justify their witness to your nostalgia. Maybe that’s where things become interesting?

There’re two camps in the art world. One says all work is unavoidably autobiographical, so you should be aware of this and use it. The other argues that art should never be autobiographical. You’re left stuck in between, wondering what to think.

SJ: Would you say this is a problem your grappling with in your work at the moment?

LW: Yes. I can see that because my biography is informed by a lot of political events and ideology, it can also be ‘publicised’. I have a lot of books and objects connected to my parents that carry a personal nostalgia but also have a wider historic significance. They contain both the private and the public within them.

Whilst at the HISK I’ve begun keeping a lot of these objects on a table in my studio as a way of referencing them – not directly in my work; but just allowing people to see them alongside it. It feels like an interesting development and I’d like to think more about how the objects can start to become part of installations that contextualise the drawings, my process and my interest production/reproduction.

Lisa Wilkens - Human Problems In Industry (2018, install shot) Galerie Mitte

SJ: Could you talk a bit more about production and reproduction?

LW: Over the last year I’ve become very interested in work and the disappearance of manual labour, chiefly from an industrial context. There’s so much about the rise of unemployment in the news and how this is partly caused by jobs being replaced by machines, which raises lots of questions around the value of labour. This in turn connects to my own practice; making really photorealistic reproductions of photographs using an outdated process (drawing) is a useless task in a way. It’s highly time-consuming and the type of paper I use disintegrates very quickly. The value lies in being with the image in the moment; spending time with it, finding out what exactly is in it and translating it by your own hand into another medium.

SJ: The value lies partly in the labour itself.

LW: Yes, exactly. There is value in making, in action, in producing, in creating, in doing. It reminds me of the work of the German artist Hanne Darboven who created a system of number-based drawing. The images she produced hold no meaning outside of her system; the meaning lay only in the act of doing.

There is an intrinsic meaning and value created through human action and self-direction.

SJ: A value that exists outside of an economic system?

LW: Exactly. This connects to the current discussion around Universal Basic Income (UBI). Many are concerned that its introduction would lead to people just sitting around all day watching television, but I think that would only happen for about a month and then you’d get so bored you’d start looking for things to occupy your time; seeking out the kinds of ‘doing’ that actually interest you personally or that you find another kind of value in. From making art, to running a poodle salon or taking care of your grandma.

UBI is a really old idea going back centuries, but I think we’re actually starting to near a point where technology could start to abolish the need for a lot of basic jobs. Somehow, we seem hesitant to actually make that revolutionary step however, and trust humans to do something meaningful with their lives without the need to earn a living.

My own drawings work as a catalyst; they allow me to think about these topics in a non-theoretical way, and they provoke conversation with others. Most people are astonished when they learn that the images I make are hand-drawn without any special equipment. They really struggle to believe a human could have these skills. When I explain that I studied drawing for four years they are a bit more accepting, but there’s still a sense of uncertainty. With training and discipline you can achieve great things, but that process takes time and can be very difficult.

SJ: I like how you describe drawing as allowing you to approach these ideas in a visual, non-theoretical way. Do you think this offers something that a more rational or intellectual framework doesn’t?

LW: Yeah, my thinking process when I’m drawing is almost cyclic or meditative. When you remake an image, you have to constantly check and compare the original with what you have, making countless tiny decisions until you eventually end up internalising the original. I find this opens a space in your head where all of a sudden you are free to think about when and why the image was made, how it found its way into the publication in which I encountered it, why the publication itself was made, who its audience was and what impact it had.

At the HISK I’ve been really struck by the prevailing assumption that you’re either a conceptual artist or a technical artist; and that if you’re technically skilled, your practice can’t possibly be conceptually interesting. For me, the concept is generated through the technique. The decision making involved in drawing makes it a conceptual process.

Lisa Wilkens - Unite, Chinese Ink on Found Paper (2016)

SJ: It’s interesting that people struggle so much to believe your drawings were made by a human hand. I feel like the training you received on your scientific illustration degree was to a level of technique and precision that isn’t very widely available any more. Would you agree?

LW: Yes. I think it was partly discovering how rare my training has become that led to my interest in process. That’s where my criticism comes from. Having any technical skill (not necessarily connected to art) that you had to master and perfect over time gives you a confidence and sense of meaning. It provides a way of connecting to an identity that is formed through it.

The situation in the UK is probably very similar to the rest of Europe where the arts are no longer considered to be useful, whilst maths, sciences and maybe languages are given complete emphasis. For me it should be the other way around. Machines can do the science and programming; what’s going to be useful in the future is independent thinking, creativity and the ability to make decisions based on a uniquely human understanding.

SJ: Yes, it seems very misinformed.

That leads me to ask what prompted the leap from scientific illustration into visual art?

LW: After finishing the course in Switzerland I moved to Berlin and began working as a scientific illustrator. It was around this time that I began to realise how my understanding of science had changed over the years. Before going to university, I had thought of it purely in terms of facts and objective truths, but now I know the opposite is the case: science is based on temporary models of understanding and ‘the latest research’. In a way, converting a model into an illustration fixes the concept down and makes it appear far more static than it really is. I also started wondering who first invented a lot of the conventions that we use to visually represent scientific ideas. By simply replicating these, they start to affect the way an idea is perceived and evolves. I began to feel strangely complicit in the process and wanted to instead start using drawing as an epistemological, investigative tool.

SJ: You no longer work within a scientific reference. What led you to the images you use now?

LW: Whilst I was studying in England, I spent a period working part-time in the Economic and Politics Library at the University of Cambridge. The space is limited there, and they get a lot of new books in each year, so older ones, considered out of date and no longer used, often went on sale. Like with the decline in traditional technical skills, I became interested in how ideas could be so easily discarded or become no longer of interest and ended up buying a lot of what was being thrown out.

The most recent body of work I made, WHY WORK (2017), was based on images from a book called Human problems in industry (1946), which came from the Cambridge library and was part of a wider series of monographs on higher management titled ‘The new democracy’. The text talks a lot about the importance of work following the aftermath of the Second World War, when people were feeling destroyed and in need of a sense of purpose, order, stability and contribution to the rebuilding of society. This resonated with my interest in labour, but I was also very struck by the emphasis on hands across many of the photographs.

Hands convey a sense of dexterity, tactility and connection, and form something of a through-line in my work. In The Shadow of an Unseen Power – an exhibition I presented at PAPER in 2015 – I used hands to bring something tangible and relatable to the show’s invisible subject: nuclear power. Then, in my Unite (2016) series, which is based on a practical advice book from 1946 (just two years before the NHS was founded) called First Aid in the Home, there are lots of hands taken from images showing how to correctly hold someone who’s been injured. The title of the work relates to the thought at the time that if the state looked after its people, they would also look after each other.

Lisa Wilkens - The Invisible Medium, Chinese Ink on Found Paper (2015)

SJ: You’re currently showing Unite at Saatchi Gallery as part of Into A Light (28 Sep-28 Oct). The exhibition is described as “bringing together the work of eight artists who use the idea of fantasy, but not in a fantastical way.” How do you see your work in relation to this?

LW: For me, the idea of the fantasy resonates with utopian thinking and the ability to imagine an alternative, better future. I think that in order to be well as a society, we need to return to a more caring, collective ideology, but for a lot of people at the moment this sounds like nothing more than a dream.

SJ: If we don’t dream, what hope do we have of ever making anything better?

LW: Exactly. There’s a very strong assumption that human nature just wants to look after his or herself, and the idea that we are social animals is crazy or has been proven to be wrong because communism failed. But I don’t agree.

I’m glad that fantasy and the fantastical are coming back into fashion. A lot of fantasy and science-fiction writers are highly political people. They use fiction to imagine a different world and model their ideas for alternative forms of society.

SJ: Do you define yourself as Marxist or Communist?

LW: I haven’t read any Marx and am only just starting Das Kapital now. It’s very depressing because it not only tells of so much injustice during the time it was written, but also reminds me of the situation for many today – Amazon workers for example, people in the gig economy or those who have to work four jobs just to sustain their family. I think that’s why a lot of Marx’s ideas are coming back into circulation.

There’s a beautiful chapter on communist desire/leftist melancholy in Jodi Dean’s The Communist Horizon (2012) which combines the political theory with an emotional aspect, which I think is also very important. It really helped me to understand that it’s not so much whether you’re a Communist or a Marxist that’s important, but whether you have a desire for justice and societal community.

SJ: What’s your experience of studying at the HISK been like?

LW: Really useful – and also massively exhausting! You’re encouraged to constantly question your own practice, which is good but sometimes I wish I could just hide in a corner and make my own work without having to think so much about it. But there’re always interesting things happening, and I’ve met some incredible artists along the way.

SJ: You’re just reaching the end of the course. What are your plans going forwards?

LW: I might head towards Berlin in the long run, but recently I’ve been wondering if I should use the next year to travel around a bit. I can make my drawings anywhere – all I need is a desk and some light.

I’ve just come back from a residency in Narva, Estonia on the Russian boarder – the very end of the European Union in a way – and would like to go back and spend a bit more time there if possible. My sister lives in New York so I wondered about visiting her as well, and then perhaps applying for another residency in Brussels. So, a year on the road! Which sounds really exciting but spending a lot of time on your own is also quite daunting. Once you overcome the initial fear however, it releases a lot of strength. I’ll see how I feel in a couple of weeks.

Interview by Sara Jaspan