Activism on Paper

by Greg Thorpe

Still from 120BPM (Robin Campillo, 2017)

Paper has possessed both an artistic and political dimension for as long as it has existed. The more widely available it became throughout the world, the more that it could be used in a dialogue with power – both by artists and political change-makers. Over time, the relationship between paper, art and political activism has evolved in myriad ways. In this article, writer and artist Greg Thorpe sets out to survey a few examples from the late 20th and early 21st centuries, and discusses the role paper plays in his own practice based around HIV/AIDS activism.

Paper/technology/activism

Political activist and writer Angela Davis cautions against a simplified telling of the American civil rights movement – one that traditionally favours tales of individual heroism over stalwart community organising. Rosa Parks’ decision to remain seated on an Alabama bus in 1955 was a courageous action from a seasoned community organiser and part of a long-standing civil rights tactic waiting to find its moment. Absent from many history book versions of the ensuing Montgomery Bus Boycott is the figure of Jo Ann Robinson of the Women’s Political Council who understood that Parks’ defiance had created an opportunity that could not be wasted.

The year-long boycott following Parks’ arrest crippled Montgomery bus services, 80% of whose passengers were Black. It was the action that elevated Martin Luther King to national prominence and kept in motion a domino effect of social change. At the centre of the historic episode was a humble piece of paper technology: the duplicating machine, or mimeograph. In the days between Parks’ arrest and her court appearance, Robinson managed to persuade a vast population of her fellow Black citizens not to ride the bus in order to protest Parks’ arrest and racial segregation. Many people were reached from church pulpits, but many more by the 50,000 leaflets that Robinson typeset and reproduced overnight. In her memoir, The Montgomery Bus Boycott and the Women Who Started It (1987), she recounts:

… we quickly agreed to meet almost immediately, in the middle of the night, at the college’s duplicating room. We were able to get three messages to a page... in order to produce the tens of thousands of leaflets we knew would be needed. By 4 a.m. Friday, the sheets had been duplicated, cut in thirds, and bundled…

Jo Ann Robinson, Montgomery bus boycott flyer, mimeographed paper, 1955 (Stanford University archive)

The Gestetner – a brand of mimeograph – was a machine beloved of activists because it allowed material to be reproduced without recourse to capitalist print factories that might otherwise refuse or censor the content. (Any small group or organisation could purchase a duplicating machine at relatively low cost, and they were small enough to be easily accommodated within private spaces.) Activist Sam Friedman loved the machines so much that he wrote a poem in 2011 titled ‘Mimeograph’:

Nor do they know the glory

of the spinning Gestetner

spitting copies galore,

the pile creeping upwards 'til the stencil

wears out,

or the joys of collation

when a pamphlet, just printed in hundreds

sits piled self upon self,

each page its own tall pile,

10 piles on a table,

3 tables the row.

… a sheet for each pile, then

step to the next,

place sheet upon sheet,

then step to the next

'til a pamphlet sits splendid

in your inky hands

and you place it akimbo

on the pile to be stapled

and circle again,

take a sheet from a pile

and step to the next,

the circle unbroken

that helped break Jim Crow and

undid the Army then un-doing in 'Nam,

the stencil, the circle,

the battle not ended…

The simple instructive black-and-white text-on-paper flyer produced by Robinson belies the laborious and timely effort that brought it into being, and the monumental change it helped to effect. This is a paper artefact that proved itself to be an historical necessity, as the decade of change that followed this major civil rights victory demonstrated. The artefact itself ought to be as familiar to us as Parks’ arrest photograph. Its power is timeless and overwhelming.

Activists have always been quick to explore and subvert new paper technologies. In 1987, the New York Times purchased its first fax machine – a technological innovation that revolutionised the global workplace, employing telephone lines to reproduce documents in locations across the world. ACT UP (AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power) was New York’s uncompromising band of AIDS activists, many of whom were tech-savvy artists, office temps or both. They made a sworn enemy of the NYT whose criminal underreporting of the AIDS epidemic fooled many New Yorkers into believing the spread of the virus did not represent a crisis until it was too late.

ACT UP member Sarah Schulman wrote in 2017:

ACT UP called them “The New York CRIMES” … when they got their first fax machine, we faxed them a mile of black paper because of their criminal refusal to cover AIDS.

Faxing a continuous ream of black paper to the NYT would force its machine to regurgitate endless sheets of pure black; wasting costly new ink and paper and preventing the shiny new technology from receiving any other communications. When I first encountered this activist ‘zap’, I immediately took it to be a potent and virtuoso art intervention: the perfect alliance of the artist/activist mind. On reflection, it’s impossible to imagine that the description is literal (it would require the equivalent of about 5400 sheets of A4) and so ‘a mile of black paper’ becomes something exaggerated, apocryphal and conceptual; and much of its extravagant power lies there.

[I have borrowed the exact phrase (‘a mile of black paper’) as the title for my own ongoing art practice hosting ‘teach-ins’ about HIV/AIDS and inviting participants to make related/inspired art. Where the original ACT UP activists sought to shut down communications as punishment, my work lovingly subverts this, and instead opens up a forum for voices, learning and sharing, some of which constitutes our own HIV/AIDS activism.]

Still from 120BPM (Robin Campillo, 2017)

ACT UP’s fax intervention is referenced in the 2017 French film, 120BPM, which focuses on a range of actions carried out by the New York group’s sister organisation, Act Up Paris, during the 1990s. Rather than ‘a mile of black paper’, the Parisians opt for a smarter abridgement: a single loop of paper that travels perpetually through the fax machine’s send-tray, reproducing itself endlessly at its destination – in this case, a pharmaceutical company which, while people with AIDS were dying, was delaying the release of its latest HIV research in order to achieve maximum glory at a forthcoming conference. The fax trick was designed to spill endless paper duplicates bearing the activists’ message into the heart of the corporation, daring to be ignored.

[The dream for my own ‘mile of black paper’ action is to reproduce this protest model: faxing participants’ art to multiple spaces around the world for recipients to keep and take home, be uplifted or enraged by, secrete into library books and clothes shops, plaster in phone boxes – do whatever with, wherever they are.]

Paper/material/money

Some paper money is fiat money, meaning that it has no intrinsic value. That is, the paper used to create the money is not worth very much in terms of its value as a raw material. Most paper money is fiat money, and its value comes from what it represents rather than what it is. … Most paper money only has value because people want it. This idea is what made beaver pelts, shells, peppercorns, tulip bulbs and other things into money at various points in history. (‘Paper Money’, investinganswers.com)

Chris Burden, Diecimila, colour photoetching within green library cloth portfolio, printed on both sides of handmade Don Farnsworth paper, coloured pencil additions by artist and printers, 1977 (Crown Point Press Archive, Museum purchase, Whitney Warren Jr. Bequest Fund in memory of Mrs. Adolph B. Spreckels)

More than gender, or perhaps even language, money is the social construct that rules us. Set up by Bill Drummond and Jimmy Cauty in 1993, K Foundation’s infamous action – K Foundation Burn a Million Quid (1994) – perhaps represents the consummate anti-capitalist art statement; one that will only get richer the closer we come to capitalism’s demise. The first impact of the work is a painful imagining of what one might otherwise have done with £1M. The second, more lasting effect, involves the realisation, not that the artists attach an ascribed value to these wads of paper, but rather that they don’t. (As it happened, they also discovered cash doesn’t burn that well. The action took a long time and was tedious to execute. The audaciousness was in the concept: the damp funeral itself was all that capitalism deserved.)

The group of activists who burned £35,000 of (fake) bank notes outside the British Home Office in 2016 to challenge unjust immigration law had at least a gestural relationship with K Foundation. We comprehend the audacity of burning money in part because of the legacy of the K Foundation Burn a Million Quid action. In other words, the vocabulary of burning money (real or fake) becomes a form of art language that activists can readily tap into, to dramatic effect.

Michael White, Scarecrow Lion Tinman, 2016-17

Along similar lines, a series of works (2016 –) by Glasgow-based artist Michael White uses Zimbabwean banknotes as tiny canvases onto which he paints scenes from Frank Baum’s The Wonderful Wizard of Oz (1900). Baum’s story is taken to be an allegorical response to the devastating US economic collapse of the 1890s. A century later, a similar economic depression in Zimbabwe caused hyperinflation and eventually led to the demonetisation of the very dollar bills on which White presents his work. Likewise, American artist Chris Burden’s piece Diecimila (1977) reproduced Italian 10,000 lire notes in such perfect detail that they could easily have been spent as tender. A triumphant piece of transformative satire occurred the moment his work became worth than the money it mimicked. These works serve as elegant reminders that if money is merely paper, how delicate might the edifice of capitalism itself be?

Activism on paper

New York artist Rachel Schragis interrogates the line between art and activism with urgency and alacrity (and lots of paper), describing her practice as “drawing out diagrams of our complex world, and collaborating with organisers and communities to strategically catalyse the power of art.” Her works often simultaneously chronicle and plan for community activism and direct action, using complex hand-written diagrams to describe intersectional struggle. After being schooled in activism by Jews for Racial and Economic Justice, Schragis spent years working with the People’s Climate March, as well as producing work for/with/about Black Lives Matter, Occupy Wall Street (her Occupy Wall Street Flowchart (2011) became an internet sensation), and other campaigning groups.

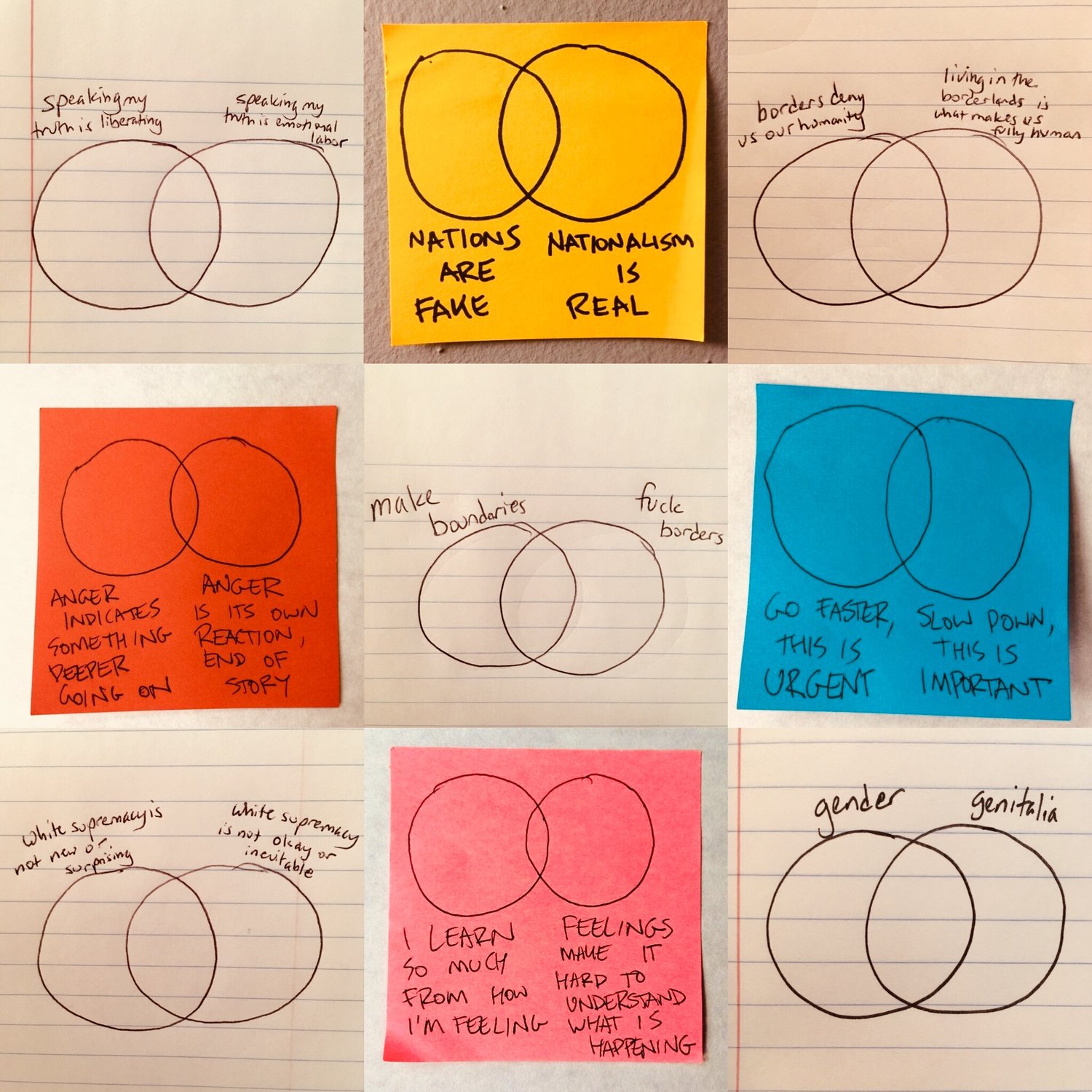

Rachel Schragis, Trump Matrix For Coping, Post-its and ink, 2017 – present

One of Schragis’ effective mediums is the paper scroll – ironically also one of the first historical manifestations of paper as a material. The scroll is an artefact that can be read and handled communally, and, crucially, added to as movements develop, stories unfold, and collectives move closer towards their goals. Confronting the Climate: A Flowchart of the People’s Climate March (2016) is six ft in length, while One Question (2012–present) is around 90 ft long and growing.

Schragis’ other favoured media include familiar office materials such as Post-it notes, flip-charts, flowcharts and Sharpies. Her works in these media capture the intensity of thought, planning, possibility and debate that any activist will recognise. Some, such as Vent Diagrams (2017 – present) and Trump Matrix for Coping (2017– present), embody the high anxiety of life in the right-wing dystopia of Trump’s America. They also offer temporary relief from this reality; either through presenting the possibility of empowerment, or by inviting participants to name and plot out their pain and confusion, make plans, and ultimately overcome. Put simply, they offer us hope.

Rachel Schragis, Vent Diagram, 2017

Throughout all of the works above, paper provides a dynamic language for art and politics to speak to one another. From the simple flyer that beat Jim Crow, to activist art-thinkers remaining a step ahead of new paper technology, to the high concept/low drama of burning banknotes, to Schragis’ complex living testimonies of activist struggle; paper’s radical history will continuously be brought up to date.